|

|

|

Quarry Press _________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

Old Scores, New Goals |

||

|

THE STORY OF THE OTTAWA SENATORS

BY Joan Finnigan |

||

|

|

|

Quarry Press _________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

The Legend of "The Shawville Express" |

||

|

"If I were building a new team and were

given my choice of all the players I have seen in action, I would select

Finnigan as one of the wings. He was a perfect coach's player; he could

score, patrol his own wing defensively and, as a penalty killer,

he had few equals." — Frank Selke, Behind the Cheering |

||

|

I was born in Ottawa in 1925, the eldest child of Maye Horner and Frank Finnigan, both then aged twenty-four. The year before, my father, known then throughout the Ottawa Valley hockey circuit and later throughout the hockey world as "The Shawville Express," had signed his first National Hockey League contract for $1,800 per season with the Ottawa Senators. Bonuses from Frank Ahearn, owner of the Senators, brought my father's salary for that first year up to $3,400. Prior to turning pro, my father had worked as a lineman for Bell Telephone in Pontiac County in Quebec and, according to Valley legend, was up a telephone pole when the long distance call came up from Ottawa proclaiming to the whole countryside "instamatically" that Frank Ahearn of Ottawa was calling Frank Finnigan of Shawville. Someone ran from the Chinese restaurant on Main Street to tell my father. For years afterwards one of my mother's constant refrains was, "Oh, if only he had stayed with the Bell! He wouldn't have gotten a swelled head, and he wouldn't have taken to drink, and he wouldn't have got in with all those dreadful people . .. and we wouldn't have . . . " The meteoric and chaotic life of the professional hockey star would have been bypassed for the more orthodox predictable life of the Big Company employee with what seemed to her, I am sure, all its enviable advantages: the punctuality of nine-to-five hours, the holidays with pay, the certain pension at retirement age, the "safe" life away from the constant threats and emotional dangers of living in the limelight. |

||

|

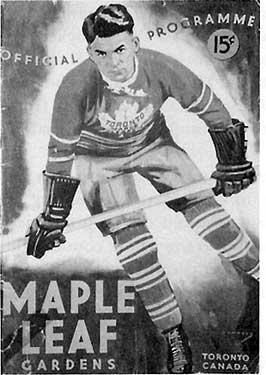

Frank Finnigan, "The Shawville Express," sports the uniform of the Ottawa Senators with the distinctive "O" crest and black, red, and white stripes. Finnigan played for The Senators for over a decade, winning The Stanley Cup in 1923-1924 and 1926-27. |

|

When The Senators disbanded in the early 1930s, Finnigan was sold to the Toronto Maple Leafs, where he starred on the 1932-33 Stanley Cup team with fellow former Senator Frank "King" Clancy. |

|

Even though my father was a national idol in an era when the country seemed to have very few, he chose to live in Centretown Ottawa on McLeod Street, first block west of Bank Street, in an unpretentious one-bathroom house. Our middle-class neighborhood was home to such future celebrities as Lorne Green, Fred Davis, and Paul Anka. I suppose my father could have chosen a more prestigious area of the city in which to raise his family. But he had wanted Centretown, he told us later, because "It was close enough that I was able to walk to work." |

|

Frank Finnigan rode the Push, Pull, and Jerk Express from Shawville to Ottawa where he became a hockey legend and gained his nickname "The Shawville Express." |

|

|

Many other local hockey heroes would travel down the Ottawa Valley to become Hockey Hall of Fame legends playing for The Senators. The Pontiac train made twenty-six stops at stations like this between Ottawa and Waltham. |

|

|

|

||

|

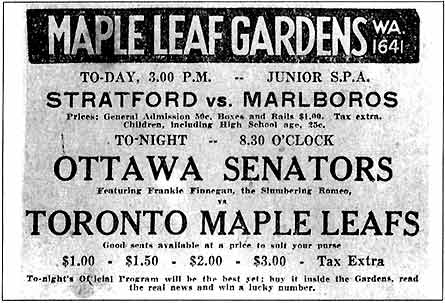

Yet he was never known to walk to work — or anywhere else, for that matter! He always drove one of his annual succession of new cars three blocks over to Argyle Avenue where the old Auditorium stood in those days on the site of the present-day ymca. There, the only professional hockey club in the history of the Capital City, the Ottawa Senators, had their home base, practiced and trained, hosted the National Hockey League teams in an international circuit which included the Toronto St. Pats, |

|

|

Pedlars with horse and cart sold their wares along the streets of Centretown Ottawa. Pictured here is Ben Polowin and his horse Jenny. |

|

Frank Finnigan's youngest son Ross rides his tricycle in front of the family home on McLeod Street, Both Ross and his brother Frankie retained considerable memorabilia of their father's hockey career. But it was John who kept the scrapbooks — source of data and photos for this booh. |

|

|

|

||

|

the Montreal Canadiens, the Montreal Maroons, the Chicago Black Hawks, the Boston Bruins, the New York Americans, the New York Rangers, and the Detroit Red Wings. Two years after I was born, the Ottawa Senators won The Stanley Cup; my father, a wet-behind-the-ears rookie brought down the telephone pole to inject new blood into the playoffs, had scored the winning goal. "

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

the games on radio. They collected gum cards

with an avidity that verged on mania and forced the rest of us to swallow

two-by-three squares of stale bubble gum, or let it go to waste. My

brother John made scrapbooks of all the newspaper clippings and magazine

writings in which my father appeared. While my brother Frankie began

playing in earnest in leagues that led to the N.H.L., John sold programs

at The Auditorium, both to earn himself some money and to keep himself

within the inner sanctum of hockey. |

|

|

Hockey heroes like Frank Finnigan endorsed every product imaginable, from Aylmer tomato juice to Dunlop tires, from Beehive com syrup to R.J. Devlin and Biltmore hats. Their image appeared not only on the sports pages but in consumer magazines and on public billboards in every hockey town. |

|

|

||

|

up and carried them away. My father disappeared from sight. The crowds surged around us like an ocean, almost tearing me from my mother's grasp. I was torn between tears and anger. Why were they bearing my father away like a piece of flotsam? He was ours. Not theirs. Or so I thought.

|

|

Frank Finnigan is shown here beside one of his annual sucession of new cars given to him by the automobile dealer as payment for his endorsement. |

|

|

|

||

|

Who was that?" she would demand. "How dare

they call you 'Frankie' when they don't even know you!" To which my father

would patiently reply, "I don't know who it was. They know me, but I don't

know them. Everybody calls me 'Frankie'. They call Howie Morenz 'Howie'.

They call Joe Primeau 'Joe'." |

|

Ottawa Senators — like Frank Finnigan — sometimes cut a dashing image office, attired in the latest fashions, supplied by clothiers and furriers in return for their endorsement. Hockey was business even back in the Roaring Twenties. |

|

|

|

||

| School. It was a cold, sunny, brilliantly blue January noon hour in which my grade was playing off for the girl's championship of the school. To this day, I can recall the feeling of floating effortlessly up the ice, stick-handling my way through the entire opposing team (most of whom were still skating on their ankles and their asses), scoring time after time as the crowd, lined up around the boards of the outdoor rink, roared their approval. |

|

|

|

Frank Finnigan was billed as hero wherever The Senators traveled — in Toronto, New York, Boston, Montreal, Detroit, Chicago, and even Pittsburgh. |

|

|

||

|

On one of these scoring rushes I went past the principal, a stately Mr. McNab whom my mother always described glowingly as "a scholar and a gentleman." As I passed him I heard him say, "Look at that girl go! She's just like her father!" This compliment offended me, I remember, for I was a girl in an age when girls were girls and boys were boys. I never played hockey again.

|

|

Frank Finnigan was the last of the Ottawa Senators living when this portrait was taken by photographer Eva Andai of Shawville, Quebec. Something of his spirit — and something of the character of the old Senators — can be seen and felt here. |

|

|

||

|

When N.H.L. commissioner

John Zeigler and the Board of Governors awarded an expansion franchise to

Ottawa on December 12, 1991, my father shared the limelight with the new

owners. "Without the support of Frank Finnigan," one governor was heard to

say, "Ottawa wouldn't have been awarded the franchise." Frank Finnigan,

"The Shawville Express," was scheduled to drop the puck at the Senator's

first home game in October 1992. |

|

|

Sporting the uniform of the new Ottawa Senators team while attending the N.H.L. Board of Governors Expansion Meeting in Florida in December 1990, Frank Finnigan lends his support and his image to the franchise. |

|

|

||

|

Finnigan starred. Headline

after headline in The Ottawa Citizen and The Journal

proclaimed his prowess and finesse — as well as the talents and courage of

Alec Connell, Hec Kilrea, Frank "King" Clancy, Frank Nighbor, Harry

"Punch" Broadbent, Cyril "Cy" Denneny, George "Buck" Boucher, Eddie

Gerard, and their teammates. |

|

At Frank Finnigan was always quick to remind everyone, the Ottawa Senators were once a proud team, winners of nine Stanley Cups before disbanding in 1933-34 — and will continue to be a proud team when they return to the N.H.L. for the 1992-93 season. |

|

|

|

||

|

I have compiled this story of the Ottawa Senators. The story begins up the Ottawa Valley, in the cradle of professional hockey... |

||

|

|