|

Toqued, furred, wrapped in buffalo robes, this merry group of young people might well be on their way to cheer their local hockey team on to victory. | |

|

The Cradle of Professional Hockey

|

||

That professional hockey was conceived in the Ottawa Valley was no accident. Geography, climate, character, and good old-fashioned wealth conspired to nourish what soon became Canada's national spoil. The Ottawa Valley is a unique homogeneous area, as large as England, the watershed for the mighty Ottawa River and its twenty-six tributaries stretching from Montreal to Bancroft, from Brockville to Timmins. Following the first waves of explorers, traders, and settlers into the St. Lawrence River Valley, subsequent newcomers flowed up the Ottawa to settle on both the Quebec and Ontario sides of the river. Most Ottawa Valley settlers chiefly Irish and Scots immigrants of little means made their living from the land, scratching out a subsistence from farming during a short summer season, supplemented by winter work in the lumber industry, felling tall white pine, driving timber down river, sawing lumber at the many mills throughout the region. This industry was founded by families, the Gillies of Braeside, the MacLarens of Buckingham, the Boyles of Maniwaki, the Conroys of Aylmer, the McLachlins of Arnprior, the Barnets and the O'Briens of Renfrew, and J.R. Booth of Ottawa. The lumbering industry also fostered legendary lumbering giants of the Ottawa Valley like Joseph Montferrand (Big Joe Mufferaw), Mountain Jack Thomson of Portage-du-Fort, Wild Bill Ferguson of Calabogie, Big Michael Jennings of Sheenborough, Cockeye George McNee of Arnprior, the Twelve MacDonnell Brothers of Sand Point. Timber money was often instrumental in fostering hockey in The Valley M.J. O'Brien, for example, founded the National Hockey Association and was the first team owner to try to "buy" |

|

Toqued, furred, wrapped in buffalo robes, this merry group of young people might well be on their way to cheer their local hockey team on to victory. | |

|

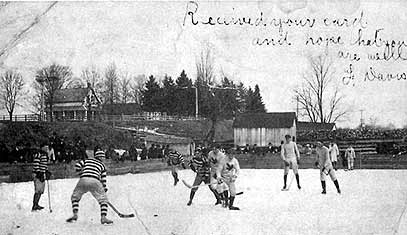

An afternoon hockey game most likely, on Saturday or Sunday, being played on the Fort Coulonge rink and their opponents in the white uniforms have come up the line from Quyon. |

|

The Stanley Cup when he formed the Renfrew Millionaires. And the heroic character the lumber giants assumed in legend was transferred to hockey heroes like Hockey Hall of Fame members H.H. "Harry" Cameron, F. H. "Hughie" Lehman, and Frank Nighbor of Pembroke; Edouard "Newsy" Lalonde and Cyril "Cy" Denneny of Cornwall; referees M. J. "Mike" Rodden of Mattawa and J. Cooper Smeaton of Carleton Place; and founding owner J. Ambrose O'Brien of Renfrew and Frank "Cyclone" Taylor, enticed to play for the Renfrew Millionaires by O'Brien wealth and cunning. Perhaps because of the

long, cold winters with no shortage of water to freeze into ice rinks,

perhaps because of the kind of |

|

Father and daughter fry out their improvised sail, created to hasten their skating speed over the smooth frozen surface of the Ottawa River.

|

|

|

Every hamlet, every village, every town, every mine in the Ottawa Valley had a hockey rink. This one at the Starelle Mine near Sudbury is certainly wired for night games.

|

|

|

"sporting" character the lumber industry created, the Ottawa Valley became the cradle of hockey in Canada, providing the various amateur and professional leagues the Amateur Hockey Association, the Eastern Canada Association, the Canadian Amateur Hockey League, the Federal Hockey League, the National Hockey Association, and the National Hockey League after 1917 with nearly 50% of their players between 1880 and 1920. |

|

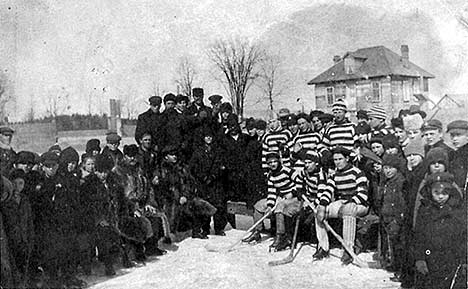

This old photograph is of Fort Coulonge's first hockey team and their supporters, many of whom traveled the long cold miles by horse and sleigh to Quyon, Shawville, Portage-du-Fort, to cheer their team to victory. Note the more affluent members of Fort Coulonge's "sporting people" in their fur coats and hats. |

|

The Valley also stocked

the great Ottawa teams the Rideau Rebels, the Ottawa City Hockey Club,

the Silver Seven, and the Ottawa Senators with some of their greatest

players. During this era, the Ottawa Valley was a ferment of amateur

hockey. Cross-roads hamlets tried to equip and field teams to play

neighboring hamlets and rivalries grew up between villages supporting

pickup teams. Small towns built and regularly iced outdoor rinks, some

with lights strung around the perimeter for night games. The speedy and

reliable post office of those clays delivered challenges to rival teams,

and fans laid heavy bets. The sportswriter was born, reporting for small

town weeklies and big city dailies. Governors-General in the Capital and

Horatio Algers in the lumbering and mining towns of the Valley became

promoters and financiers of hockey teams. Leagues were formed and

re-formed; teams organized and disbanded. Cups were cast in pure silver.

|

||

|

|

|

|

Quyon Hockey team, about 1906-07. Bottom row, LEFT TO RIGHT Herby Moyle, Billy Boland. Second row Frank Doyle, William Pimlott, Pug Pimlott, Angus McLean (later to run the Quyon ferry for fifty years), Pete Moran. Third row Eddy Grant, Milliard Walsh, Frank Kennedy. |

|

|

sweaters and team

equipment, as well as very scant traveling expenses, maybe tickets to

travel on the train from Perth to Brock-ville to play there and come back

the same night. It was a landmark experience for young men if there was

ever entertained the thought of slaying overnight in a strange and far-off

hotel. |

||

|

|

| Fort Coulonge Hockey Team, 1930. Benny Duke, Tony Davis, Theo Spotswood, Ed Davis, Lionel Chevrier, Cuddy Harry, Frank Davis, Tommy Jules, Rossie Coll, Tommy Larmeau. This team actually traveled all the way down the Valley by train, no doubt to play Cornwall, Ontario. |

|

against teams from Ottawa. They had a good baseball field, a splendid fairgrounds, and, even as far back as 1907, they had a very good indoor hockey and skating rink. The rink, which was in a substantial building, was situated on the Desert River Road, midway between the two villages. As a matter of fact, it was the first of three closed links built on the same spot. Two of them burned down. I think it might be in order here to recall some of the more prominent players of that era. In hockey, there were the Gilmours (Billie, Suddie, and Ward), Jim Nault, Redmond Daly, Jim Quaile, Mike Lawless, Wally Lawless, Bob Mooney, Gray Masson, Lionel Bonhomme, Fred Rochon, Joe Gendron, et cetera, et cetera. The quality of hockey played in that era was of very high caliber. It was a notable fact that Billie and Suddie Gilmour had both played for the Ottawa Silver Seven, the world's champions of that day. The other members of the Maniwaki Hockey Team were relatively good . .. Hockey at Maniwaki was perhaps more glamorous than the other sports. I believe one could divide the hockey of the early days into three separate eras. The first group, who played from about 1907 until about 1919, was comprised of Billie and Suddie |

|

Unfortunately, other than "Maniwaki Hockey Team," there is no documentation for this photograph of players seated in front of a group of proud, sartorial men who must have been the team's backers, perhaps coach and manager. Whatever the date, Maniwaki has won and everyone is sporting ribbons and proudly displaying the championship cup. |

|

|

Gilmour, Mike Lawless, Fred Rochon, Redmond

Daley, Joe McFaul, Bob Mooney, and Tresor Godbout. Their competition was

mainly from Ottawa city teams. The Valley teams of that day were must not

good enough to compete. During all of this period Jim Donovan was the

referee, and sometimes the visiting teams didn't get the best of the

decisions. The second era, which lasted from 1920 until 1926, was graced by

such players as Ward Gilmour, Charlie Logue, Jim Nault, Wally Lawless, Jim

Quaile, and Lionel Bonhomme. This group, with the exception of Wally

Lawless, had previously played senior hockey in either the Montreal or the

Ottawa City League. I have forgotten to mention Gray Masson, who played for

Maniwaki for four years. Gray, Jim Nault, and Ward Gilmour had previously

played in the Ottawa City League. Jim Quaile had played with McGill

University in the Intercollegiate, and Charlie Logue had played for Loyola

College in Montreal. They were no mean group of hockey players and could

entertain fast company. They had some illustrious years and brought great

credit to the town. |

|

|

|

Shawville, out of all proportion to its size, was consistently renowned as a hockey town, perhaps because it was so well supported by its businessmen. This is a 1911 photograph of the Shawville Pets, backed by Shawville merchants. LEFT TO RIGHT Frank Finnigan, Hoddy Rennick, Albert Chisnell, Art Turriff, Archie Dagg, Lyal Hodgins, Rock Findlay, Clark Cowan. Finnigan is only eleven in this photograph but is already playing with fourteen- and fifteen-year-olds. |

|

sweaty clothes, and your teeth would start to

chatter and you'd start to shake, and the chills would set in, and, even

worn out from playing a whole game, the only way to survive was to get off

and run behind the sleigh. Sometimes there were buffalo robes if we were

lucky and you'd crawl under those and continue shivering. I often wonder

how we didn't die of pneumonia. But we were young and tough, then.

When we got to

the Westmeath rink, we quickly laced on our skates and jumped on the ice for

a warm-up that was really a warm up. But the Junior team, for some reason or

other, perhaps they were afraid of us didn't show at all. So some of the

townsfolk, feeling badly about our long journey and the let down, scrambled

around town and picked up members of the Westmeath Senior team. Guys

fifteen, sixteen, even seventeen. It was 10:30 by the time we got the game

started. Naturally, we lost. But only by a score of 7-3. It was one o'clock

by the time we finished the game, and the diehards went home to their warm

beds. |

|

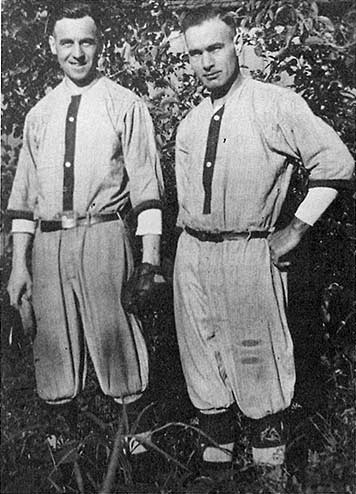

The great Ottawa Senator, Frank Nighbor, right, in baseball garb, with Dave Behan, amateur sportsman and tireless worker with young boys athletic clubs in Pembroke. In Nighbor's day, before the advent of modem day methods of training and fitness techniques, summertime sports like baseball were a preferred way of "Keeping in shape. "Nicknamed the "Pembroke Peach," Nighbor starred on five Stanley Cup winning teams and was the initial winner of the Hart and the Lady Byng trophies. |

|

money. How much money he collected Billy never

admitted. But there were guesses that he wouldn't have to work for a long

time. |

|

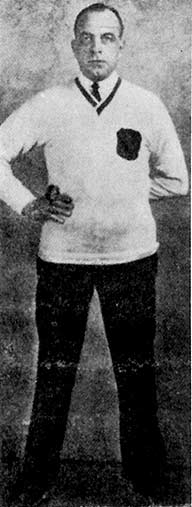

Born in Pembroke in 1895, F. H. "Hughie"Lehman (left) was an outstanding netminder for twenty-three years, thus earning the nickname, "Old Eagle-Eyes."He played on eight Stanley Cup challenging teams, but won only once with the Vancouver Millionaires in 1914-15.

|

|

|

|

||

|

the playing area. However,

there exists no record of any player being seriously injured during play

around them. |

|

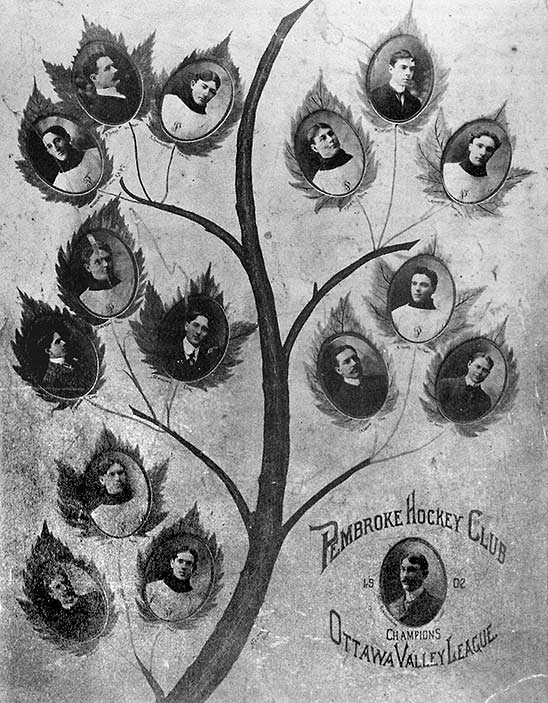

This Ottawa Valley League Champion team from Pembroke included players W. Wa!lace, S. Shaugnessy, T.Jones, L. Kennedy E. Howe, B. McPhee, J. Puff, L. Rnnsonand almost as many executive members, namely D. Burns, W.D. McLaren A. Thomson, J.E. Wallace, J.R. Grieve, S. St. James, H.J. Macrie, and President E.W. Cockburn. |

|

|

||

|

Morrisburg was Cornwall's first hockey foe in lively games with Billy Peacock in goal and Billy Adams, Billy Turner, Arthur Mattice, Fred MacLennan, John Milden, George Pettit, Fred Degan, and James Cameer in the lineup. Stuart Rayside of Lancaster and Randy McLennan of Williamstown donned Cornwall uniforms during the holiday season when they were home from university. This team was good enough to hold down |

|

Hockey in the Ottawa Valley was a sport not only for men. Shown here is the Pembroke High School Girls Hockey Team of 1921-22. Back row, LEFT TO RIGHT M. Wilson, S. Thomson (Manager), B. Anderson, A.J. McDonnell (Coach), J.Jones. Front Row N. Gourlay, I. Fraser, J. Wilson, S. Workman, D. Walker. |

|

|

|

||

|

both the champion Winnipeg

hockey team and the famed Montreal Shamrocks to tie scores in exhibition

games. |

|

One of Frank Finnigan's heroes C.J. "Cy"

Denneny (left) was born in 1891 and played some of his junior hockey with

the O'Brien Mine Team in the Cobalt Mining League. He played for five

Stanley Cup teams and was coaching the Ottawa Senators in 193233 when

they folded. Edouard "Newsy"Lalonde (right), born in Cornwall in 1888, was one of Canada's outstanding lacrosse players of all time. A brilliant scorer, Lalonde was also one of the roughest players of his day in the N.H.L. Feuds between Lalonde and Quebec Bulldogs Big Joe Hall helped fill arenas. |

|

|

|

||

|

where they played against such teams as

Ottawa's Montagnards and the Montreal Wanderers. In succeeding years

Cornwall won both the Senior and Junior Citizen Shields in the Ottawa Valley

Hockey League. In the St. Lawrence League, Cornwall Canadiens carried off

honors again.

|

|

M.J. O'Brien was born at Lochaber, Nova Scotia in 1851. He moved to Renfrew, began railway construction at an early age and later diversified into mining development in northern Ontario and Quebec, becoming one of the leading Canadian capitalists of his time. He was a backer of the famous Renfrew Millionaires. |

|

|

In 1909 when the Eastern Canada Association was the only professional hockey league and Renfrew's application for admission was rejected, J. Ambrose O'Brien almost single-handedly organized the rival National Hockey Association and was instrumental in founding the Montreal Canadiens to play in the new league. |

|

|

||

|

future wife, Jennie Barry. They were married in

Renfrew at St. Francis Xavier Church, 1883. O'Brien, as a contractor, went

on to build parts of the Intercontinental Railway all over Canada, including

the North Shore Line of the CPR between Montreal and Ottawa, the K&P Line,

and lines in the Maritime provinces. M. J. was away from home most of the

time, but built Jennie a substantial house on Barr Street in Renfrew where

she wished to stay. The servants were hired and the babies were born.

Because Ottawa and Montreal were his business centers, M. J. began to use

the Russell Hotel in Ottawa and the Queen's Hotel in Montreal as his homes

away from home. His eldest son, Ambrose, was initiated at an early age into

the mysteries of the O'Brien involvement in lumbering and construction, and

later mining. |

|

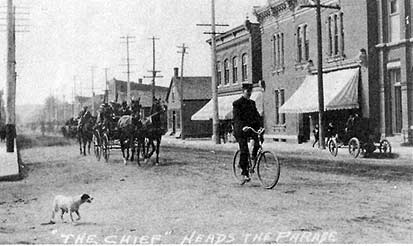

One of Renfrew's renowned characters, policeman Barney McDermid, accompanied by his faithful dog Spot, leads a parade down Raglan Street. Behind him is a carriage carrrying civic dignitiaries, followed by a military contingent of the First World War. |

|

|

||

|

On December 18,

1908, a meeting was held in Renfrew and the decision made to form a

professional hockey team. A few days later a meeting in Ottawa reorganized

the Federal Hockey League with professional teams from Renfrew, Cornwall,

Smith Falls, and Ottawa (the Senators.) Thomas Low, a local MP and later a

minister in a Mackenzie King cabinet, was Renfrew representative. Jim Barnet

was chosen vice-president and Ambrose O'Brien, M.J.'s son, executive member.

Bill O'Brien (not related) was chosen as the Renfrew trainer and Bert

Lindsay, professional goalkeeper, hired along with Larry Gilmour, Ernie

Liffiton, and Bobby Rowe. |

|

The Renfrew Millionaires of 1909-10 challenged the Montreal Wanderers for The Stanley Cup. |

|

|

|

||

|

The roads up The Valley were closed off with

snow in those days, as Gorman reminisced later in the Weekend Magazine

in 1957: "One of my assignments while covering sports for The Citizen

was to catch 'The Timberwolf Special' to Renfrew to cover the hockey games

there and then catch the return train to Ottawa with my story at 5 a.m." |

|

A Cyclone Taylor bubble gum card, today worth

much more than its original one cent selling price. Hockey great Cyclone Taylor played on two Stanley Cup teams the Ottawa Senators in 1908-09 and the Vancouver Millionaires 1914-15. He starred, briefly, for the Renfrew Millionaires. |

|

|

|

||

|

these championship games we played at home in Listowel. But the O.H.A., for some reason or other, decided we should play a "sudden death" game in Toronto at the old Mutual Rink, and the Listowel people were up in arms because they wanted to see this game. After all, they'd paid good money and supported us all winter. But the O.H.A. insisted on us playing the Beechgroves in Toronto and they beat us 8-6 for the Ontario Junior Championship. I think the trophy at that time was called the John Ross Robinson Trophy, and we missed it. Anyway, that game playing the Kingston Beechgroves in Toronto, the arena was filled with people and again I just happened to be well, you have to be good some nights and not so good other nights I scored nearly half of those goals. And that game in Toronto set me up. The teams then started to look to Listowel for a player. I started out as a defenceman and became a forward. Yes, it is true that I wore a toque to cover my bald spot. I lost my hair on the back when I was young and I was sensitive about it. But lots of fellows wore toques in Eastern Canada because of the cold weather, and that would make a good enough excuse any time. When I belonged to the Renfrew Millionaires, M. J. O'Brien spared no expense for us. They paid us good salaries and when we traveled he gave us the best, and the town of Renfrew entertained us. We were little gods, but the boys behaved themselves and we went into the finest homes in Renfrew and were welcomed. O'Brien spared no expense. Everything was lavish Winnipeg goldeye until the New York people bought them all, lock, stock, and barrel. Yes, I was a "sixty-minute man." We all were in those days. I wouldn't want to make any comparisons with the players today. I can only say I wouldn't want to play in this game today. For one thing, you're only getting out there for two or three minutes. It suits them. They were brought up to it, and they don't know any better. But we were on for sixty minutes and we paced ourselves for that sixty minutes. And we could go! I've always said that any player between the ages of sixteen and thirty who can't play sixty minutes "bang" of hockey, there's something the matter with him. I know that if he's physically fit, it would be a joy. I know in my case it was a joy. You paced yourself, just naturally, just the same as a man running five miles or twenty miles. He goes so far so fast and then so far at a different pace. You prepared yourself for that sixty minutes on the ice. I don't think there was the violence in my day, but mind you, I remember in my day there were two players killed. I wouldn't want to give you the names because the fellow that killed one of them is still living in Ottawa today that would be away back in 1904 or '05. Just a hit over the head; it was a lad from Cornwall. But we only had one referee in those days and he couldn't see everything. This hockey that's being played today, I don't know where it ever developed. Even little boys I'm honorary president of the British Columbia Hockey Association, have been for some years even those little boys are steeped with the idea of playing rough. They think it's alright. In some cases I think the parents and their coaches are as much to blame as anybody else. I've sat at little games there in Vancouver where you'll hear a mother scream, "Hit him, Billy! Kill him! Kill him!" Now, if a mother is talking like that to her children, well, it's got to stop. We in Canada killed lacrosse by rough play that's field lacrosse and just the same they'll have to change their mode of playing in hockey. Hockey is such a splendid game: the skating and the skill and the speed. Anybody can play rough, they don't need to hit one another. I played a lot of lacrosse, too, and I remember a game one Saturday afternoon in Vancouver. In those days there were no cars and very few people, except the rich, went to summer cottages, and the Saturday afternoon lacrosse games especially the 24th of May holiday one would draw enormous crowds. Well, this Saturday afternoon Westminster had come over to play us, the Vancouver team, and the game was just getting nicely under way with the place packed with yelling people, and some violence occurred I can't remember what, though our manager and owner, Mr. Con Jones, just pulled his team right off the playing field. Scores of people said they'd never go to see another lacrosse game. But when Westminster and Vancouver lacrosse teams played one another, it was nothing but a donny-brook, always a donnybrook! And I feel hockey is in danger of doing the same thing. They could easily do it. There's people across Canada and I venture to say the ladies don't want that kind of thing oh no, it has to be stopped. They'll penalize those players until... Of course, the salaries are a hundred times what we made. Conditions were different in my day when you could buy a pound of butter for seven or eight cents and eggs for three cents a dozen. But the salaries are still too high by comparison and it's going to end. It's ending already. The W.H.A. was responsible for that.. . Newsy Lalonde, Lester and Frank Patrick, Joe Hall they were the greats of my day and they compare very favorably with the greats of today. I don't think the training has improved that much at all. And as for the equipment, we were just as well protected. Some of the teams now, sure they have half their team off half the time with hurt knees or smashed ankles. I never had an injury in all my years of professional hockey. I never had a wound worth putting me out of business even for a game . . . I suppose at this age I could put down my philosophy of life. People speak of "self-made" men. Well, let's take my career, just the hockey. First, Toronto wanted me to go with the Marlboroughs. I don't know what made me go up to Thessalon; then, when I came back, the Wanderers wanted me to go to Montreal. But I often think if I had gone with the Wanderers, I would never have met Mrs. Taylor, and that was one of the greatest things of my life. I wouldn't have had these wonderful children that I have today. What is that saying? "Man is destiny?" I don't think you are in charge of your won destiny. I think you're guided by your family or from Up Above. No, the saying is "Man is master of his own destiny." Well, I wonder what prompted me to make that decision about hockey? There was this inner voice that none of us can explain. But every move that I've made seems to have been to my advantage and to my pleasure, and I'd say to my success too . . . I have fourteen grandchildren, and one grandson, he played this winter, and he's junior A. The team he played with was Langley, which is about thirty miles from Vancouver. He went to school in Langley for the last two years. He was picked as the best all-round player in the league and there were five colleges in the States writing to him to go to them and one of them was Michigan, where I played. They were very anxious to get Mark to go there, just out of, well, 1 guess out of the connection. But he's decided to go to Grand Forks, North Dakota; they're giving him a four-year scholarship. Some of them wanted him to play in the National Hockey League here, but he took our advice. He can have that four-year scholarship; he's only seventeen, and when he's finished he'll be twenty-one and he can still go and play in the N.H.L. That four-year scholarship is worth sixteen to eighteen thousand dollars, so that's one boy we've steered in the right way, and not by force just by example, I suppose. With my grandchildren I'm very careful to make it advice, not instruction. I'll tell you one of the nicest things that's happened to me lately. One of the television stations out of New York, they wanted to get somebody, an older person, the oldest person they could find the oldest hockey player they could find and when they phoned me and I said I was ninety-one years of age and that I had played hockey up until 1911, they said, "My God! You're the fellow we're looking for!" Now all I did, and it was one of the nicest things I ever did, I went out with Brian McFarlane you know him? and we skated around the ice, arm in arm, talking as we're talking now about hockey and things in general. People that saw it thought it was one of the nicest well, I enjoyed it more than anything I ever did on television. And it was surprising the number of people that saw it and communicated with me and said, "Mr. Taylor, that was a lovely, quiet, homey little program." And it didn't last very long: seven minutes. When I quit hockey, sure, I missed it, but at that time we had three little children and I was all tied up with family life. I missed it, sure, but you have to acquaint yourself with the changing conditions of your life. What have I got to look forward to? Me. At my age! Heaven, I guess! Yes, I know they say I am the only man who ever scored a goal skating backwards. Well, let them say it, let them say it.

Miss Lillian Handford of Renfrew remembers The Millionaires and Cyclone Taylor in this light:

I almost got to see the game that Cyclone Fred Taylor was -supposed to have skated backwards and scored the goal. Cyclone Taylor. Well, you see, my father sold pianos where Dr. Ed Handford's office is now the Robertson Company from Ottawa sold pianos in there years ago. Well, Dad sold records as well in there, and the Renfrew Millionaires used to come in there in the afternoons when the Renfrew kids would be using the hockey rink and they'd listen to the records. Yes, the Patricks and the Fitzpatricks and Cyclone and all these men. 1 was always coming in from school and I always went through the store to see what I could see there. But, anyway, Dad had tickets for all the hockey matches, including the Renfrew Millionaires, and he and Mother used to go, and they used to put bricks in the oven to heat them and then take them to the rink to keep their feet warm. This night Mother was sick, and I begged so hard to be allowed to see them play and they wouldn't let me go, but that was the night I can remember my dad coming home and telling my mother that Cyclone skated backwards and scored a goal! Charlotte Whitton always said that it was absolutely true and she could have remembered it, even been at the game, because she was a little older than I was and, besides, some of the Renfrew Millionaires boarded at the Whittons her mother kept a boardinghouse. But you see, the Renfrew Millionaires were only a year or two there in Renfrew and they wouldn't really remember the people. They might have remembered my father, though, because he was always very nice to them and let them play the records. And they were all Red Seal records and Caruso and all high-class music, and they all just loved that music. They'd stay by the hour and play them. |

|

Hero worship of "Cyclone" Taylor is clear in the name of this Renfrew Women's Hockey Team. |

|

|

|

||

|

I remember my parents arguing about a proposed Renfrew Millionaires game in Cobalt. I know there was a great discussion as to whether my father could afford to go, take the trip. And, of course, hockey players were in and out of the shop so often, and he'd taken pictures of them all. I must say that the players were always very nice with you when you came in. Of course, I used to come into the store any time I could, but I got shooed through and up the stairs. They were good-looking young men. Anyway, he really wanted to go and see this game, and my mother persuaded him to go ahead. They won, of course, and he came back, thrilled to death. He'd got on the train to come home, the train was empty, and he was one of the first ones in, and on the side of his seat he found two twenty-dollar bills. He came home and presented my mother with them. She said, "Where did you get those? Were you betting on those games?" He said," I didn't have to." There were reserved seats in the Renfrew arena. They put them in when the Millionaires came. Before that, I think, it was just benches really, and everybody grabbed a seat where they could. But I must tell you a story that is sort of related to all this hockey. After the Second World War, my Uncle Alex was a great one for telling stories. He had two sons and a daughter, and the older son, Ken, was stationed in Ottawa for a little while and he wrote and asked me if he could come up to Renfrew and see me. Ken had never stayed in Renfrew and would like to come and |

|

Lillian Handford's father made considerable income in portraiture, but photograph postcards were also a big part of his livelihood. Mr. Handford designed this Easter card using the Renfrew Millionaires as a big selling point. The card is addressed to Master Silas Reed, Eating P.O., London, Out., and says: "This is our good team of hockey players, the bunch who played in New York last Saturday night and won score 9-4. Edward." |

|

|

|

||

|

spend a weekend. My mother was dead by this time and Dad and Herb, my brother Doc Handford, and I were here. And there was a Pembroke-Renfrew hockey game being played. First of all, we couldn't get parked on Argyle Street at all, so we had to park a long distance from the rink and walk to it, all the way along I was saying "Goodnight" to people I knew and they were saying, "Good evening, Miss Handford," and then at the rink there were all sorts of friends and acquaintances talking to me, kidding me. So, we got into the rink. I had the tickets, so I was meeting them all, ushers and everybody. And when we finally got sitting down, cousin Ken said to me he'd lived in Toronto all his life he said, "Lil, do you know everybody in Renfrew?" And I said, "Well, not quite, Ken. Why?" He said, "Do you know you spoke to every single person you met all the way here?" And I said, "Well, I teach school here and they have all gone to school." That was the first thing that hit him. Well, then the game started! He said that he always thought his father had been making up stories about the Pembroke and Renfrew hockey matches. But you know, there wasn't one thing was left out in that game he saw that night. We had a man in town called Bob Scott and he, at the rink-side, all night long, would yell out, "Get him! Get him! Get him!" You know, keep it up all the time the other team would have the puck. And we were sitting not too far from the penalty box, and hanging over the penalty box was a drunk with all the vocabulary and all the verbal abuse, and what those players sitting in that penalty box had to take was unbelievable! And then this big Pembroke player fell on the ice and hit the back of his head so hard that it bled, and when they were taking him of the ice he left behind this trail of blood all across the ice, and it froze there, and when Ken came home with me he said, "I wouldn't have believed what I saw tonight. My father told us these stories about them being laid out and carried off the ice." But everything happened at that game that night you would have thought it had been staged for him. The crowd was wild. There was a good gang down from Pembroke. There were a couple of fights in the crowd. To the day he died, Ken never came to visit that he didn't say, "I'll never forget that hockey match you took me to in Renfrew!"

/ interviewed Tommy Barnett in 1980 at his home in Renfrew, Ontario, shortly before he died. He was one of the last surviving members of the Harriett lumbering dynasty, a family which had had great influence in The Valley not only through its lumber operations but also as great breeders of fine horses and barkers of hockey development and expansion:

We also had the Renfrew Millionaires, the great hockey team of 1910-11. Actually, the two chief financial backers of The Millionaires were my grandfather Barnett, who never went to a game in his life, and Senator M.J. O'Brien. And then there were the others who put up money as well. So much has been written but never any credit given to the other people who put in money. The books for the team were always kept in my grandfather's office; Mr. Hardy Cox was the treasurer and he was my grandfather's head bookkeeper. My uncle George Barnett, he was the president of the team, and Ambrose O'Brien was vice-president. And my uncle Jim Barnett, he was one of the chief backers of the team as well. And they all thought nothing of betting two, three, four, five thousand on a game in those days. Oh, I recall the late Dr. Bill Box of Renfrew saying that when he was going to school he was quite a good hockey player on the Renfrew collegiate team and he would be invited to go along to the games. My grandfather, father, and uncles would maybe take three or four young Renfrew fellows with them to a game in Cobalt my uncles were interested in mining up there, as well as lumbering and Bill Box told me about my uncle Ben winning five thousand dollars in one of the games up there. Well, five thousand dollars in those days was like fifty thousand dollars today . . .

One of the young men. who followed the careers of those Ottawa Valley hockey heroes was Frank Finnigan, himself soon to became another hockey legend from The Valley:

I knew by the time I was nine that I was going to be a professional hockey player. Of course, we didn't have any radio or television then, but I used to save my money and buy every newspaper from Ottawa that I could get hold of. I wasn't very good at school, but I could certainly read the sports pages of The Ottawa Journal and The Ottawa Citizen at a very early age! The train used to come into Shawville at six every evening, and as soon as I would hear that whistle blow I would head down to Joe Turner's confectionary or Doc Clock's drugstore and get my papers. So would a lot of other people. I read about Cyclone Taylor of the Renfrew Millionaires. They say he was the only man who ever really scored a goal skating backward. Joe Malone of the Quebec City Bulldogs scored forty-four goals in twenty-two games. I can remember I was impressed by that. There were all my Ottawa heroes: Eddie Gerard, Jack Darragh, Percy Lesueur, George Vezina, Gordie Roberts, Harvey Pulford, the Smith Brothers (Alf and Tommy), George "Buck" Boucher, Hod Stewart. And the others: Cy Denneny of Cornwall, Didre Petrie of Montreal, Frank Nighbor of Pembroke, Larry Gilmour of Renfrew, Scotty Davidson of Kingston, Art Ross of Queen's University. Eventually I played with some of my heroes like Frank Nighbor, Sprague and Odie Cleghorn, Punch Broadbent. And in time I got to know some of the greatest people ever associated with the early game Frank Ahearn, Frank Selke, Dick Irvin. |

|

|

The Shawville rink, one of the first in Western Quebec and scene of many of Frank Finnigan's first hockey victories. It fell down in 1972. |

|

|

||

|

When I was young growing up in Shawville the whole world was a rink. A hockey rink, not a skating rink. When I first started to play hockey, I played on the ponds and on the crust. We'd have a big rain and it would freeze and make the crust just the same as ice. Yes, it would be just the same as ice; it would carry a team of hockey players or a team of horses. And then we had the ponds and the creeks. When we got a bit bigger we had the small lakes, which we kept shoveled of in the winter. Then every second house in Shawville would have a little rink in their back yard. It wouldn't be too big but you could still play on it. The John Cowans on Back Street at the old Shawville Equity they published that paper for a hundred years had a great big summer kitchen and sometimes we would flood that and use it. It was the first covered rink! And then you'd have the streets to skate on when you'd have a rain and it would freeze. You played shinny on the streets in the winter and road hockey on the streets when the ice and snow was gone. Well, then in 1913-14, Shawville got its covered rink one of the first if not the first in the Upper Ottawa Valley. W.A. Hodgins, general merchant; Duncan Campbell, gentleman; Chris Caldwell, hotel-keeper they put up the money for the materials for the rink, but everyone in town gave their labor free. There was Standing Room Only for three to four hundred people. We even had night games. The first lighting arrangement was oil-burning lamps strung above the ice surface on wires. The lamps would smoke up, go out, and often be shot out by the players sometimes on purpose to keep the other team from seeing too well when they were winning, sometimes just plain accidentally by a high shot. The Shawville rink fell down one day in the 1970s. Now, covered rinks have some advantages, but not many. You have to wait for rink time these days, so you don't get nearly as much hockey as we did in my learning days. We just moved from one kind of rink to another perpetual motion. If one pond wasn't good enough, we moved to a creek and so on. I played hooky from school all the time to play hockey and I wouldn't recommend that! I think everybody should get an education. I had a tough time. We didn't have any fancy skates and equipment. I bought my first single-blade pair from Cedric Shaw for five dollars when I was thirteen years old; they were secondhand. Before that I played on double-enders. We were always collecting from the Shawville merchants for money for team sweaters. We had to supply your own hockey sticks. That was hard for me. The good ones, made of natural wood with clear shellac, were fifty cents each. The cheap ones were painted red to cover up the knots. We used frozen horse balls for a puck when we couldn't afford a rubber one. Most of the time. By the time I was thirteen I was playing in the Pontiac League for Shawville against Campbell's Bay and Quyon. In those early days league size was limited by the number of miles a horse could travel per hour. We used to drive by sleigh to the games in Campbell's Bay and Quyon, three or four hours each way. We'd be in a lather of sweat after playing a full game and then out into the freezing night and the cold, cold sleigh. If we were playing Campbell's Bay and had collected from the merchants of Shawville we could catch the Push, Pull, and Jerk, get there in time for a game, and stay overnight at Smith's Hotel. That was the Big Time. While I was in the Pontiac League we began looking for more competition, and we used to bring up teams from Ottawa for exhibition games, teams that were playing in the Ottawa City Senior League. Big excitement in town for twenty-five cents a ticket! There were four to six players on those early Ottawa teams who could have turned pro, if there had been enough teams to turn pro with. But there were only four teams in the N.H.L. at that time: Montreal Canadiens, Toronto St. Pats, Hamilton Tigers, and Ottawa Senators. Then the league expanded, the New York Americans took over the Hamilton franchise, and Boston Bruins came in. |

|

|

Although he could have become a professional hockey player, J. Cooper

Smeaton, M. M. (left) of Carleton Place chose his career as referee for

more than twenty-five years in the N.H.A. and the N.H.L. Until his

retirement in 1937 he was N.H.L referee-in-chief. He was elected to Hockey

Hall of Fame in 1961. Born in Mattawa in 1891, M.J. Mike Rodden (right) made an impact on the sporting world as player, coach, sportswriter, and referee in football, lacrosse, and hockey. In 1944 Rodden became sports editor of the Kingston Whig-Standard and until his death worked tirelessly for the establishment of Kingston's Hockey Hall of Fame. |

|

|

|

||

|

We were always looking for a hockey game, anywhere, any time, anyhow, in those younger days. We liked to go out to the smaller towns like Portage-du-Fort, Bryson, or Elmside and have an exhibition game. Of course we needed a livery team to get there sometimes four dollars. So we'd go to W.A. Hodgins and he'd put down for so much. And we'd go to John Shaw he was a storekeeper in town and then we'd go to Chris Caldwell he had the hotel and he'd put down for so much and finally get enough to pay for the livery team and we'd be off. Well, one of the referees who refereed in our league, Bill Smith of Ottawa, saw that I had possibilities. Word got around to Dr. Eddie O'Leary of Ottawa University, and he asked me to go down to Ottawa and play for Ottawa U. in the Senior City League against Montagnards, Ottawa, Munitions, and Victoria. You think that kind of thing only goes on today? Well, I played two seasons for Ottawa University, 1920-21 and 1922-23, at fifty dollars a game! Yes, the Coulsons J.P. and his sons, Harry and D'Arcy, who owned the old Alexander Hotel and who backed the Ottawa U. team they paid me fifty dollars a game. I was enrolled in the university as a "commercial student." But I never went to a class. That's true. You can see a picture of me yet in the hall of the old Arts Building at Ottawa. I had some other interesting offers, too. When 1 was young and still playing amateur I had an offer to go to Pittsburgh and play on a kind of "scholarship" they would put me through for a doctor or a dentist. It was a semi-pro league there, it wasn't a minor league, but I can't remember what the university was. They offered me pretty good money. I had the same kind of offer from Queen's University at Kingston they would have paid me to play hockey there and put me through whatever degree I wanted. But I didn't have the education, you know, at all. Remember I quit school at Grade Nine. Towards spring a team came up from Ottawa, the Royal Canadians, from Ottawa's Senior City League. Shawville played an exhibition game with them that night. When I went up to Gibson's Restaurant for coffee and sandwiches after the game, there was a telegram there for me from Frank Ahearn, owner and president of the Ottawa Senators. He wanted me to go to Ottawa the next day and talk contract. This was five games before the playoffs, mind you. I went down to Ottawa the next day by train and met Mr. Ahearn and we talked contract. I signed the contract only an hour before I got into my new Ottawa Senator sweater, Number 8. It was a three-year contract for eighteen hundred dollars a year. I was a green kid from the country and he never held me to it, gentleman that he always was. The next year he upped it to thirty-five hundred dollars, then forty-five hundred, then fifty-five hundred, with bonus all the time. But he could have held me to it if he had wanted to. It was a big jump from Shawville to the red, white, and black of the Ottawa Senators. I was nervous and didn't get my bearings at first. It was the playoffs, too, against the Canadiens. I suddenly found myself up against players who were as good or better than I was. No weaknesses in those lads Frank Nighbor, Buck Boucher, Clint Benedict, King Clancy. In those days The Ottawa Valley was the cradle of hockey. I think at that time the valley developed at least fifty percent of the hockey players in Canada. Even in the Western league there would be a majority of players from the East on the Edmonton, Regina, Calgary, Saskatoon, Victoria teams.

The roll call of legendary hockey players raised on the rinks of the Ottawa Valley goes on and on ... Bill Cowley of Bristol, Ken "Cagie" Doraty of Stittsville, Bob Gracie of North Bay, Dave Trottier of Pembroke, Johnny Sorrell of Chesterville. Many of these players would travel up or down The Valley to join the professional ranks of the Ottawa Senators, merging their rugged Valley character with the finesse of native Ottawa players like Hall of Fame legends Frank McGee, Harvey Pulford, Frank "King" Clancy, Harry "Punch" Broadbent, Jack Darragh, Billy Gilmour, Harry "Rat" Westwick, Clint Benedict, Syd Howe, Tommy and Alf Smith, Gordon Roberts, Eddie Gerard, William H. "Hod" Stewart, Alex Connell, Frank and George "Buck" Boucher, Bruce Stuart, E.B. "Ebbie" Goodfellow, and Hector "Hec" Kilrea, to create some of the greatest teams in the history of hockey. Ottawa Valley boys would also stock the teams that challenged The Senators for supremacy . . . |