|

The Champions of The World |

||

|

"It was nothing but the best for us, the best food, the best traveling, the best accommodation the Waldorf Astoria in New York, the Leland in Detroit, the Congress in Chicago, the King Edward in Toronto."Frank Finnigan |

||

|

When the National Hockey League was created in November 1917, the Ottawa Senators were a founding member, along with four other teams Montreal Canadiens, Montreal Wanderers, Toronto Arenas, and Quebec Bulldogs. During the next decade, The Senators won the Stanley Cup four times in 1919-20, 1920-21, 1922-23, and 1926-27. Senator great Frank Nighbor won the first Hart Memorial Trophy in 1924, presented annually to the most valuable player in the N.H.L., and the first and second Lady Byng Trophy in 1925 and 1926, awarded for gentlemanly conduct combined with a high standard of playing ability. Senators Punch Broadbent in 1922 and Cy Denneny in 1924 won the Art Ross Trophy for leading the league in scoring. The"Roaring Twenties" were indeed the glory years of the Ottawa Senators, but long before the" Dirty Thirties" ended in World War II, The Senators had disbanded and the heroes of the capital city of hockey were dispersed around the league, sold to the highest bidder. Players of such high caliber as Frank Nighbor, Frank "King" Clancy, Clint Benedict, Harry "Punch" Broadbent, Cy Denneny, Alec Connell, Íåñ Kilrea, George Boucher, Harold and Jack Darragh, Eddie Gerard, Allen Shields, Bill Touhey, Hooley Smith, Frank Boucher, Syd Howe, and Frank Finnigan would not wear an Ottawa sweater in the N.H.L. after 1933-34. For the first seven years of their time in the N.H.L., The Senators were managed by Tommy Gorman, coached by Pete Green, and led on the ice by Frank Nighbor. Although The Senators struggled |

||

|

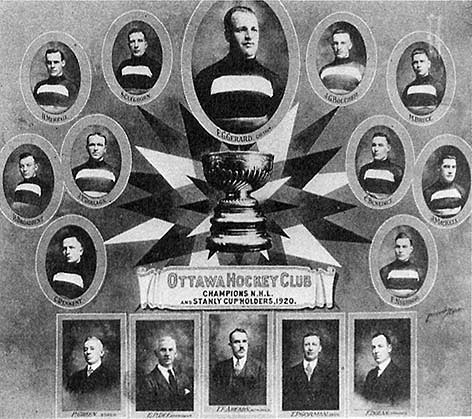

Led by Captain Eddie Gerard, the Stanley Cup champion Ottawa Senators of 1919-20 included H. Merrill, S. Cleghorn J.G. Boucher, M. Bruce, H. Broadbent, J.P. Darragh, C. Benedict, J. Mackell, Ñ. Denneny, F. Nighbor and executives P. Green, E.P. Dey, Ò.Å. Ahearn, T.P. Gorman, F. Dolan. |

|

through the 1917-18 and 1918-19 seasons, they returned to championship form the next season, winning the N.H.L. league title and defeating Seattle Metropolitans in The Stanley Cup, which was still a challenge cup at that time. Bill Galloway recounts the Ottawa Seattle series as follows: Seattle Metropolitans journeyed East to meet Ottawa, at Dey's Arena, for The Stanley Cup. Dey's Arena had natural ice and the outcome of the series depended heavily on the weather. Ottawa won the first game on a soft ice surface on March 22nd by a 3-2 margin before a sellout 7500 fans. The second game on March 24th was again won by the Senators, 3-0, on a water covered rink. The third game on March 27th was a farce. With more than an inch of water covering the ice, Seattle came out on top, 3-1. It was decided to move the remaining game to Toronto's Mutual Street Arena where artificial ice was available. Seattle won the first game in Toronto 5-2 but were soundly defeated 6-1 on April 1st, 1920, and Ottawa left for home, clutching their sixth Stanley Cup. |

|

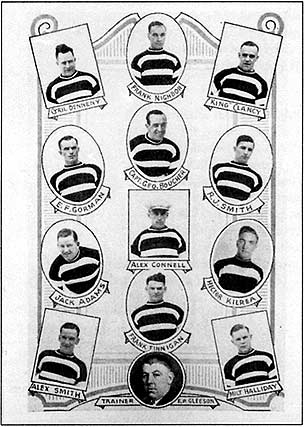

Ottawa Senators Stanley Cup Winning Team, 1923-24.

Back row, LEFT TO RIGHTE.P. Dey (President), Clint Benedict, Frank Nighbor, Jack Darragh, Francis "King" Clancy, Tommy Gorman (manager), Pete Green (coach).

Front row Harry''Punch " Broadbent, George "Buck"Boucher, Eddie Gerard, Cyril "Cy"Denneny, and Harry Helman. |

|

|

The Senators superiority on the ice and Ottawa's love for the team had been translated by the Gorman family into a box office success. Over 7,000 fans from a total Ottawa population of 70,000 regularly packed Dey's Arena on Laurier Avenue, paying $1.25 to $5.00 for a ticket. In 1919-20 there was even talk that Ottawa could support two N.H.L. franchises, and it was rumored that the Montreal Canadiens team would move to the capital. Hockey mania swept the city, such that even Parliament emptied out early on hockey night in Ottawa. The Ottawa Citizen reported on how The Senators drew fans from throughout the region: "Fifty coon-coated young bloods, Shawville's elite (rye whiskey flasks, no doubt, stuck in their inner greatcoat pocket) swept down to Senator games on the Push, Pull and Jerk from'up the line.'" The Senators won the Stanley Cup again the next year as their dynasty built. The team was led in scoring by Cy Denneny, who placed second in the league, two points behind Newsy Lalonde, his fellow Cornwall native. As Bill Galloway reports, 'The Senators successful defence of the the Cup was unexpected: The Senators finished a dismal third in the league in 1920-21 and were not given much of a chance to repeat as Cup winners when they met Toronto, in Ottawa, on March 10, 1921. Senators showed their old form in shutting out the St. Pats, 5-0. The teams went to Toronto on March 14th and again the high flying Senators emerged victors by a 2-0 count. The Senators headed West to meet the Pacific coast champions for The Stanley Cup. The largest crowd ever to watch a hockey game in Canada to that time packed the Vancouver Denman Arena on March 21, 1921, to watch Vancouver Millionaires lose a squeaker to the Senators, 2-1. Ottawa won the second game on March 24th, 4-3, while the third game on March 28th ended in a 3-3 draw. Vancouver won the fourth game, 3-2, and the stage was set for the final contest on April 4th. Thousands of fans were turned away as The Senators eked out a 2-1 win and returned to a modest celebration in Ottawa with their seventh Stanley Cup. Although Harry "Punch" Broadbent won the N.H.L. scoring championship in 1921-22, The Senators relinquished The Stanley Cup to Toronto St. Pats, who were becoming an archrival. In 1922-23, The Senators reclaimed the Cup, led by N.H.L. MVP Frank Nighbor. The final playoff series, against Montreal Canadiens, was especially memorable, as Bill Galloway reports: The eighth Stanley Cup by an Ottawa team was won in 1923. The Senators bet out the Montreal Canadiens, who now had acquired the great Aurel Joliat, by a single point to win the championship. The Senators and Canadiens met in a two-game, total-goal series on March 7th in Montreal. Led by Clint Benedict, Ottawa shutout the Habs 2-0 in one of the wildest, dirtiest hockey games ever played in a Cup series. Sprague Cleghorn and Billy Coutu of the Canadiens ran wild, using fists, sticks, and elbows to injure and render helpless any player in a barber-pole uniform. Both Canadiens players were ejected from the game. Canadiens general manager Leo Dandurand did not wait for the league to take action. He immediately suspended both players and they were not in the lineup in Ottawa on March 9th when Canadiens beat the Senators 2-1, to lose the total goal series by a single goal. Outraged fans demanded jail sentences and banishment for life from hockey for the two Canadien ruffians, but nothing came of it and Ottawa headed West to meet Vancouver Millionaires for The Stanley Cup. |

|

Ottawa citizens welcome home their 1923 Stanley Cup winners. |

|

|

At the Denman Arena before a sellout crowd, Punch Broadbent of Ottawa scored the only goal of the game as the Senators won the first game, 1-0. The Millionaires won the second game on March 19th, 4-1, but lost the third on March 23rd by a close 3-2 score. The final game, on March 26th, saw the great Ottawa team outclass The Millionaires to win 5-1 and advance against Edmonton Eskimos who had arrived in Vancouver on March 24th and were awaiting the winner of the Ottawa-Vancouver series. Ottawa defeated the Eskimos 2-1 in the first of a best two of three series played in Vancouver. The second game was played on March 31, 1923, and saw the great, Frank "King" Clancy of Ottawa play every position, including goal, as The Senators downed the Eskimoes, 1-0, to win The Stanley Cup. Ottawa goalie Clint Benedict had been given a two minute penalty for slashing and, as he headed for the penalty bench, handed his goal stick to Clancy, saying, "Here kid, take care of this place till I get back." King Clancy followed Benedict's instructions to the letter while Harry "Punch" Broadbent scored the only goal of the game. When The Senators left for Ottawa, Frank Patrick of The Millionaires called them"the greatest team he had ever seen."The Senators arrived in Ottawa on a right, sunny day in April. They were accorded the biggest, civic reception ever given a Stanley Cup team. |

|

|

T.P.

Tommy Gorman (left) was another one of Ottawa's early Renaissance

sportsmen. He managed or coached seven Stanley Cup teams

three Senator, two Canadiens, one Chicago, and one Montreal Maroons

team. Born in Ottawa in 1886 he was for many years Sports Editor of The Ottawa

Citizen. He is honored as a "Builder"in the Hockey

Hall of Fame.

T. Franklin Ahearn (right) was the pride, the power, and the passion behind Ottawa's great N.H.L days of the 1920s. The stars of his time all held him in the highest esteem. His hockey losses were estimated at $200,000 but he said he never regretted a penny. He was born in Ottawa 1886 and died there in 1962. He, too, is a Hockey Hall of Fame inductee. |

|

Thousands lined the parade route, blocking Rideau and Sussex Streets at the rear of the Union Station as The Senators arrived by train. Fox-Movietone newsreel cameramen recorded the event for the theaters. There was no doubt, this Ottawa Senator team were worthy Champions.

At the end of the 1922-23 season, the high-flying Senators were sold by the Gorman family to a group of Ottawa businessmen headed by Frank Ahearn, whose father, Thomas Ahearn, owned Ottawa Electric and the famous Ottawa Electric Streetcar Line. Like so many entrepreneurs before him lumber barons like J.R. Booth and mining moguls like M.J. O'Brien and so many after him, Ahearn invested his fortune in his team, often risking corporate insolvency to sponsor The Senators. Thomas Ahearn was born on Le Breton Flats in Ottawa, worked as a telegraph operator for J.R. Booth, and became not only a highly respected businessman but also a well-loved Member of Parliament. To house their new team, the Ahearn's built a new 10,000 seat arena on Argyle Street called The Auditorium, which was well-served by Ottawa Electric Streetcars bringing fans to the ticket gates. They chose Dave Gill to coach the team and awaited another Stanley Cup.The Senators lost to the Canadiens in the 1923-24 N.H.L. playoffs, even though The Auditorium was packed to overflowing with over 10,000 fans for the series. The Cup was won the next year by Victoria Cougars and then in 1925-26 by Montreal Maroons. |

|

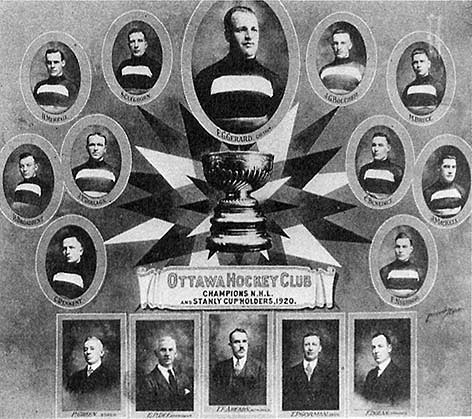

Shown here is the cover of the program for the final game of the 1926-27 Stanley Cup. |

|

|

| The program lists the starting lineup for the last Ottawa Senator team to win The Stanley Cup. | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Featured here are pages from the hand-printed souvenir program of the civic Banquet honoring The Senators. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not until 192627 did The Senators bring home the Cup again, as Bill Galloway reports:

The ninth and final Stanley Cup to be won by an Ottawa team came to Ottawa in 1927. The 1926-27 season saw ten teams in the newly expanded N.H.L. The league was divided into two divisions, the Canadian and the American sections. The Senators won the Canadian championship and met the Montreal Canadiens, led by Howie Morenz and Aurel Joliat, in the sectional final, with the first game in the Montreal Forum. Ottawa stunned the Canadiens by shutting them out 4-0 before 13,500 fans. Canadiens were odds-on favorites to win the Cup and were counting heavily on Howie Morenz when the teams returned to Ottawa to conclude the two-game, total-goal series. Over 10,000 fans jammed the Ottawa Auditorium on April 4th to see The Senators hold Canadiens to a 1-1 tie and advance to the Cup finals against Boston Bruins. The Senators traveled to Boston to play the first two games of the Cup finals. The first game, on April 7th, ended in a 0-0 draw after twenty minutes overtime. Ottawa won the second game on April 9th, 3-1, and the teams headed for Ottawa to finish the series. The third game, April 11, ended in a 1-1 draw, setting the stage for the finale, in the Auditorium, on April 13, 1927. The fourth and final game was a fairly mild affair until midway through the third period when a series of fights broke out, eventually precipitating a riot, resulting in fines ranging from fifty to sixteen hundred dollars. One Boston player, Billy Coutu, was suspended and expelled from the N.H.L. for life and never played another hockey game in the league. President Frank Calder was praised by the media for his prompt action in punishing the perpetrators.

Ottawa did prevail in the final game 3-1, with two goals by Cy Denneny and one by Frank Finnigan. The victory was celebrated at a huge civic banquet, attended by political and sports dignitaries, at the Chateau Laurier. The Ottawa Senators hockey team would have little to celebrate between this 9th Stanley Cup victory banquet and the press conference called at the Chateau Laurier in 1990 to announce the"Bring Back The Senators" campaign.

The Senators have not won a Stanley Cup since 1927 and the team began a slow collapse into ignomy the next year as rumors of financial problems with the team's owners grew.My father always claimed that Frank Ahearn was under pressure from Thomas Ahearn, his father, to get out of the risky business of backing an enterprise like a hockey team where profit was always at the mercy of the whims of the crowd. It was even suggested that old Tom wanted his money out. And so father and son were often in direct conflict, particularly since |

|

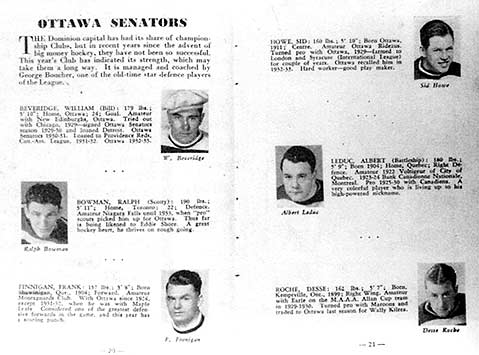

This is the last Ottawa Senators team to play in the N.H.L., listed here in the 1933-34 General Motors Hockey Broadcast Guide. |

|

|

Frank was committed to building a winning team and providing them with nothing but the best in terms of salaries, bonuses, travel, and accommodations. The Crash of 1929 and the onset of the Depression did nothing to help Frank Ahearn, and during the 1931-32 season, he suspended operations, selling some players to rival N.H.L. teams, lending out others, with the hope of re-instating the team for the 1932-33 season. |

|

|

Once-proud Senators found themselves playing for the St. Louis Eagles in 1934-35 before that team disbanded the next season. |

|

Frank "King" Clancy was sold to the Toronto Maple Leafs for $35,000, along with Art Smith and Eric Pettinger, though other star Senators Frank Finnigan, Íåñ Kilrea, Alec Connell were only loaned to N.H.L. rivals, before returning to Ottawa for the 1932-33 season. Significantly, while on loan to The Maple Leafs, Frank Finnigan helped his old teammate King Clancy lead The Leafs to a Stanley Cup victory. Ahearn ran the team for only one other season in Ottawa with a patched-up line-up that included rookie Ralph"Scottie" Bowman before transferring the entire franchise to St. Louis. The once world-champion Ottawa Senators became the St. Louis Eagles, a footnote in N.H.L. history.

An article in The Ottawa Citizen, under the heading "Buying, Selling Hockey Players Big Business Now," gives a clear indication of Ahearn's motives in "liquidating" The Senators:

Development and sale of high-class hockey players comes under the head of lucrative business. Owners of the Ottawa hockey club of the National Hockey League, now sponsoring the Eagles in St. Louis, have sold nearly $200,000 worth of talent that, except in one instance, was home recruited and developed in the last few years. The first big sale made by the club was made to Montreal Maroons, who paid $22,500 for the services of Reginald Hooley Smith, signed by Ottawa from Toronto Granites, Olympic champions of 1934. Their next trade of major consequence was the sale of Frank "King" Clancy, dashing defence player, to the Toronto Maple Leafs for $35,000 and players. Clancy was picked up from Ottawa amateur hockey and developed on the Ottawa N.H.L. team. The Ottawa club developed Íåñ Kilrea into a great left wing. Toronto bought him for $12,000 cash and players. Sid Howe was signed to his professional contract by the Ottawa team in 1929, from the Rideau team of the Ottawa City League. Ralph"Scotty" Bowman was signed prior to last season from the Niagara Falls amateur team. Both were recently sold to Detroit Red Wings for $50,000. |

| This cartoon appeared in a Toronto Maple Leaf game program during the 1932-33 season while Frank Finnigan was "on loan" to The Leafs. |

|

|

A few days later, Frank Finnigan, recruited from Ottawa amateur ranks and developed to professional stardom by the Ottawa club, was sold to Toronto for $8,000. Ralph Cooney Weiland, secured in a trade from Boston, was sold by Ottawa for $7,500; Joe Lamb brought $5,000, when first sold to Boston; and the club got $3,000 for the veteran right-wing, Cy Denneny, another Ottawa product. These are in addition to minor sales and to the value of players secured in the various trades.

In later years, my father reflected upon the collapse of The Senators, trying to understand how the glory years of the "Roaring Twenties" became tarnished by the "Dirty Thirties":

After 1927 there weren't the people to support the team. In Ottawa in the mid-Thirties there were only 110,000 to 120,000 people. We didn't start to grow until after the war, 1945. |

|

|

|

Holland Avenue that's where the streetcar ended and that was the end of Ottawa in those days. In the Thirties there wasn't a whole lot of money in Ottawa and Hull the Depression was on the federal government, Ahearn's Ottawa Street Railway and Ottawa Electric companies, Booths in Hull those were the big employers. Instead of trying to strengthen the club by keeping players like Clancy, instead of trying to find some talented new players, they folded the club. They did sign on some new players but they didn't mature fast enough to save the team. Instead of us getting stronger after our 1927 championship, we were becoming like On the other hand, you couldn't expect Frank Ahearn to give entertainment to Ottawa and not break even. After all the Ahearns were big businessmen, and they just got fed up trying to make the team soluble, watching their money go down the drain . . . St. Louis had a good rink. It was a big cattle palace and the ice surface was 220' by 100' (standard Canadian rink is 85' by 200'). There was a fence up in the stands; the black people sat on one side and the white people sat on the other side. They never packed the arena in St. Louis. Hockey was a new game. They tried a few games in Philadelphia and that didn't go over. Then a game or two in Atlantic City, but that didn't work there either.

By the end of the next season, the St. Louis team also disbanded. The Ottawa Senators name lived on, though, as the city iced a team in the Quebec Senior League . . . and dreamed of the day when a Senators team would again return to the N.H.L. and win a 10th Stanley Cup.

In another conversation, my father reflected upon these golden years which were to turn to dross as The Senators disbanded and his career reached a twilight phase:

The first year, 1923, that I played for the Ottawa Senators, we lost out to Canadiens. But my dreams came true in the 1926-27 season when we brought home The Stanley Cup to Ottawa. There was a big ceremony at the Chateau Laurier and the citizens of Ottawa gave each player an eighteen-carat gold ring with four- teen diamonds set in the shape of an O. A few years ago King Clancy's was stolen and Birk's borrowed mine to make a duplicate for him. On the Senators, King and I became great friends and some sports writers in Ottawa Eddie Baker, Journal, or Bas O'Meara, Citizen called us the Damon and Pythias of hockey. We became good friends and roomed together at the Royal York when we played on Toronto Maple Leafs, but it must have been difficult for King sometimes because he was a tea-totaller then.I was having my troubles with Tommy Gorman, the manager of The Senators and part owner with Ahearns. My wife always said that it was because he didn't like me at all. But in actual fact Gorman was a real Roman Catholic and he was upset to find out that Frank Finnigan with a name like Finnigan was an Ulster Orangeman. For that reason, and because he had a lot of power in the Ottawa Senators then, he tried to undermine me by keeping me on the bench and not playing me very much. I joined The Senators in the spring of 1923, and even into the fall of the second season, he tried to bench me, but then Frank Ahearn bought out the Gorman shares, and when Gorman disappeared, I was on my way. Ahearn was far more interested in building a good hockey team than finding out the religious denomination of his players. But there was all kinds of troubles between the Roman Catholics and the Protestants in those days, and it was too bad. It was sad. But, I believe all that is gone today. The Senators were pretty evenly split. Clint Benedict, Eddie Gerard, Jack Darragh, Punch Broadbent, Cy Denneny, myself we were all Protestant. King Clancy, Frank Nighbor, Alex Connell they were all RC's. Buck Boucher was on the fence. He married a Protestant and brought his family up Protestant so he took neither side. But we'd be arguing a little over some crazy thing and Buck would say to me,"Well, don't bother now. I'll write the Pope about it." Frank Nighbor was an RC and we always roomed together. And then Alex Connell came on the team and Benedict went to Montreal Maroons. Alex was an RC and we always roomed together. We were good friends and really got along well. And Sunday morning, if we were in New York or somewhere in the States, Alex would always get up for church in the early morning, even though he was tired out from Saturday night's game, and he'd say to me, "You lucky buggar, you Protestant. You can lie here and have a good sleep and I've got to find my way to mass." No, religion never made any difference with us. And race never did either. Once Gorman left, Frank Ahearn was in charge and we became really good friends. The Auditorium and the Senators that was pretty much Ahearn money but they had some shareholders. I couldn't say who they were. They were small shareholders who put in a little money. The Ahearns were taking a revenue off the streetcars which they owned bringing hockey followers not only to the pro games, but to the juniors and seniors as well, and anything else that was going on in The Auditorium, like boxing, skating, shows. They were taking a revenue off the streetcars to bring audiences again. Frank Ahearn, I don't think he ever told me how he got interested in hockey. I think he just liked it as a boy and then he managed some hockey teams before he got into the N.H.L. He lost money every year on the Ottawa Senators. Ottawa, even though it was the cradle of hockey, wasn't large enough to draw big enough crowds to make money enough to keep a professional team. In those days the roads weren't ploughed in winter, so the crowds dwindled in bad weather. The Depression was on and the civil servants were poorly paid. But even though he was losing money every year and his father was grumbling about it all the time Frank Ahearn was a perfect gentleman to us all, all the time. It was nothing but the best for us, the best food, the best traveling, the best accommodation the Waldorf Astoria in New York, the Leland in Detroit, the Congress in Chicago, the King Edward in Toronto. And we always had a private railway car attended by porter Sammy Weber. J.R. Booth's sons, J.R., Jr. (Bobby) and Fred they were both playboys used to be going down to New York often and they'd come into our private car and do magic tricks for us. They were really good magicians and they belonged to the Magicians' Association and were learning new tricks all the time. The club bought the best tickets for us to the best shows. We saw Bing Crosby make his debut in New York at the Paramount Theater on Broadway and we met him after the show. Ever after that he was a fan of ours and used to come to the games and sit behind the players' benches and talk to us during the games, especially to Íåñ Kilrea and me. We saw Al Jolson in Sonny Boy and when he sang "Sonny Boy" everybody cried. Sometimes the whole team would go to Harlem to hear the great jazz players, perhaps at the Cotton Club; we saw the Nicholas Brothers, famous tap-dancers, and we heard Duke Ellington, Lena Horne, Fats Waller, Cab Calloway, Count Basie. Calloway was my favorite. Some of us would go into Jack Dempsey's bar after a game across from Madison Square Gardens. Have a beer and shake hands with Jack. He was finished boxing by then and he was the front man. I used to love to tell my kids, or anybody else for that matter, that "I was in Sing Sing." Yes, Red Horner, Andy Blair, and myself, with two detectives, had the tour of Sing Sing when Hauptman was in Death Row and ready to walk the last mile for the kidnapping and murder of the Lindberg baby. |

|

|

Frank Ahearn at his summer place at Thirty-One Mile Lake in the Gatineau where he royally entertained his Ottawa Senators. |

|

I remember some of the prisoners were out on a field playing soccer but, most of all, I remember their cells a bed two feel wide and a one-and-a-half foot space beside the bed. The floors were marble and that narrow walkway beside the beds was all worn down from men pacing like animals in a cage. Chicago was a city in the grip of Al Capone and his mobsters. That was the time of Prohibition and speakeasies and bad liquor. Billy Birch from Hamilton and Lionel Conacher from Toronto both then playing for New York Americans and myself went into one of the hotels that was one of Al Capone's haunts, and we saw him there. It was a speakeasy with a dancing show. In the Brunswick in Boston we used to meet Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig on the elevators and in the lobby. Íåñ Kilrea, Alex Connell, Buck Boucher, King Clancy, and myself would talk sports with them. Frank Ahearn used to have the team up to his summer place at Thirty-One-Mile Lake in the Gatineau. It was a huge island with main lodge, cabins, boathouse, icehouse. We boated, fished, played tennis, ate, and lived like kings. There was a cook, servants, handymen .. . It's a funny thing but during my hockey career I played at the opening of three arenas. The first season I played for Ottawa |

|

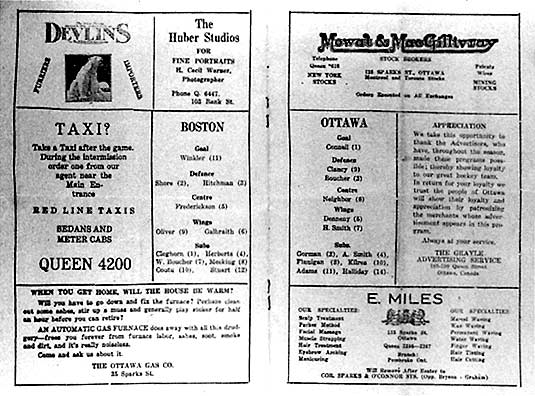

The advertisements in the programs for The Senators games appealed to both sexes. |

|

||

|

Senators in 1923-24, that was the first winter the new Ottawa Auditorium was in business on Argyle Street in Ottawa. Then in 1927 the Ottawa Senators met the New York Americans in the opener at Madison Square Gardens. At the New York opening the crowds came in their evening dresses and furs, tails, and top hats. It was the first time we had ever played in a heated arena and we all nearly died of sweat. By 1931 when the new Maple Leaf Gardens was opened on Carlton Street in Toronto, I had been traded to Toronto, so I was there for that big opening. And I have been back for the celebrations at the Gardens of both the twenty-fifth and fortieth anniversaries. It's strange to walk down a red carpet on a rink where you used to break away .. . The greatest character who lived at the Royal York Hotel at the same time I did was Harry McLean, the great railway construction man. He'd always stay there when he was on business in Toronto. McLean, you have to understand, was a giant. Except for Charlie Conacher he made the Toronto Maple Leafs look like midgets. He was about six-foot-five and would weigh about two hundred and thirty, something like Tarzan. No fat on him at all, raw-boned, all muscle, powerful to the end. I don't know when he slept, but he would come up to our door at all hours of the night and pound on it until we answered. Yell, and pound, yell out, "Get up, you bastards!" We'd maybe have practice the next morning and we'd pretend to be asleep. But he'd just roar there until we got up Conacher, Jackson, maybe myself. Nothing would do but we'd go up to his room. Sometimes he just wanted to drink he always drank Johnny Walker's Red Label but other times he wanted to eat. 1 have seen him order everything up to his room, all the food maybe, including oysters or a tank of lobsters. One time I remember he even ordered up the cook and had him cook the whole meal in his room. Another time he paid part of the Royal York orchestra to come up to his room and play for us . . . I held my own for fourteen years with the "Great Ones" Jackson, Joliat, Morenz, Clancy, Shore. To me, Morenz was the greatest. He was like a bird when he took off. Yes, they used to say I was "untrippable." I had great balance. I was a very good right wing; Selke says it in his book. Looking back on myself, I can now honestly say I was a good stick handler, a good skater, a good defensive man in a tight spot. I was hard to get at because I always kept my shoulders forward, hard to hit, and I could hang on to the puck. I had two rules: it was my puck until I found the right place to put it; and never pass to a guy who is covered. In 1937 I hung up my skates. I had played fourteen years with the best of them. In those days there wasn't the kind of training you get today. I was slowing down. I wanted to quit while I was up. I always said I would quit while I was up ...

On August 19, 1987, I went to Quyon to interview the McArras family, who at the turn of the century had run the Norway Bay Ferry. Nobody was home, so I drove past Gervais O'Reilly's house, and there he was silting out on his veranda looking for someone to talk with. Gervais is a fine fiddler and storyteller. I found him in a rare good mood:

I met Frank Finnigan not too long ago somewhere and I said to him,"What do you think of Wayne Gretzky as a player, Frank?" And he said, "Well, if we'd had him back in my time, we would have just heaved him over the boards."

Gervais then went on and told a superb hockey story about King Clancy and fellow Ottawa native Aurel Joliat, whom my father always considered a great hockey player, and certainly one of the greatest skaters who ever skated:

King Clancy really had it out for Joliat in this game and he had sworn that he was "going to get him really good." Of course, Joliat could skate so fast and stop and turn on the edge of a dime. So Clancy had missed him and missed him again, and it's getting on into the third period. So the next time Aurel Joliat came close to Clancy, Clancy headed straight for him to nail him. And Aurel, the little Frenchman, threw back at Clancy in a loud voice, "Come on, Clancy! You couldn't hit me with a handful of wet peas!"

Another time, W.J. Conroy of Aylmer told me these tales of Frank "King" Clancy:

King Clancy in later years came down to our tennis club in Ottawa, the Rideau Club, and I taught him how to play tennis. But I knew King before that. He used to come here to Aylmer and practice. He was older than I was, and he'd get onto the rink down there, and we'd all be skating around, and Eddie Gerard used to come up with him. He came down to the club and we got reunited. He was a hell of a nice chap.King Clancy, he went around with Spiff Campbell. He played for The Rangers in New York and he was a great friend of Frank's. But he was a real booze hound and Frank was a teeto-taller. |

|

Frank ''King" Clancy was perhaps the most colorful and likeable player in the N.H.L. during his playing career with The Senators and The Leafs. Advertisers rushed to gain his endorsement. |

||

|

He wouldn't touch it at all or smoke. And he was always getting poor Spiff out of trouble. Spiff threw a party for them in New York and they were all drinking and everything and when they went to leave the party there was only one coat left. Somebody'd taken Spiffs coat and there was an undertaker's coat hanging there. Spiff didn't know what to make of it, he was so mad. Frank thought that was very funny. So Spiff had to wear the undertaker's coat home. I don't know what it looked like exactly, or what the undertaker would be doing in the Club either. Maybe looking for business! Frank Clancy didn't like the nickname "King." His father was called King Clancy. I don't know whether it was his real name or not, but he was known as King Clancy, and then it just fell to Frank, and some of us that knew him for quite a few years never got in the habit of calling him that. He didn't like it and he didn't make any fuss about it, but now and again he'd drop it, and he'd say, "That's my father's name. It's not my name." He was quite a religious type, too, you know. There was a religious holiday in the summer in the Catholic church, and"King" was leading the parade down Bank Street, right in front. He wouldn't miss it; he was there every year. It was one of the big feasts and they had a parade. And he wouldn't miss that for anything! And Frank was very good to his family. His sister, she had a bit of trouble, and everything like that, and Frank looked after them, and the family down in Sandy Hill. Spiff Campbell never had a job after he quit hockey but he traveled all over the place with Frank, and Frank paid for everything. He was very good that way. After you'd finished hockey, you'd be lucky if you'd run into a Harold Ballard like Clancy did, but how many of them got that lucky! Frank was one of the lightest defencemen in the N.H.L. We always said he was just as light in the head because he'd stand in front of the CPR train coming down the track and try to stop it, you know. He was that way. There wasn't an inch of Frank's body there wasn't a scar on. He was scarred from his neck to his feet. We'd be taking a shower at the tennis club and we'd say, "Where'd you get that one, Frank?" He'd say, "Wait a minute now, I think that was over in Chicago." He never won a fight in his life. But as a defenceman, you know, his idea of stopping a guy was to stand in front of him. He'd stop the guy all right, but he'd land about twenty-five feet down the rink on his back with another scar! He was no good at tennis. He couldn't even count. I'll tell you what he did to me. We were playing over at the Rideau Club in one of the city tournaments, a handicap tournament. That means that if you had a thirty or forty handicap, you had to win three points before you started to count. And you couldn't afford to drop a point, and, of course, every kid entered the thing and they'd get out there and they just batted all over the place, and if they happened to be lucky, you were down a game. And you played all afternoon to win, you see. And Frank Clancy comes along as a referee, and I know he must have found out I was playing on one of the back courts, and he came over and he got up on this ladder and I played, I'll swear, three hours, beating a little kid that didn't know what the game was all about and killing myself. I got mad and I hit a drive and it landed far inside the line, you know. A pure fluke. Clancy says, "Out." Holy gee, what can you say? And he's sitting there nice and cool and everything and here I am running all over the court. So I won the match anybody could have, I guess and I came off and I said, "What the hell is the matter? Are you blind?" He said, "Why?" I said, "The one you called 'Out.' " "Oh," he said, "I knew you'd get that back." "Get it back!" 1 said. " I could have been out of the game by the time I got it back!" I had to play about four games to get that thing back. He was just having fun. Playing tricks really, eh? When Pine Lodge at Norway Bay first started in the 1930s, Frank and Spiff drove my wife and me and friends of ours, Cracker Bell and his wife, up when they only had one cabin and the main lodge, but Frank and Spiff drove us up about two o'clock in the morning, so we hardly knew where we were, you know. And there was a great big bandsaw blade hung underneath the floor and they hit that with a sledge at about six o'clock in the morning for breakfast. And the whole building shook. Scared the daylights out of us! We didn't know what was happening. After that we used to go quite often. They had a nine-hole course; it was just like playing out in the back pasture, but it was a lovely spot. I can remember when Frank used to drive down to Montreal from Toronto and he'd drive all night, and going down he drove so fast that he'd collect about four or five tickets on the way down. But he had to get there. I remember him telling us how many hours it took him and how many tickets he got.

For forty-seven years, until fairly recently, Charlie Kenny actively worked in a senior capacity in his family lumbering business, the McLaren Mills at Buckingham, Quebec. He has fond memories of the Boucher boys who played in this era for The Senators:

I knew all the Bouchers. They all had cottages on McGregor Lake, Frank and Buck and George. I spent more time with them than I did at home. I could tell stories by the hour; they were a great bunch. When they played with the Old Pros, they played baseball, hardball, in Ottawa. They played once a week. There was Wally Durand, George Boucher, Frank Boucher, Bill Beveridge, Boots Smith, Bill Cowley. When they'd go to the lake I'd go with them and I'd be their water boy there. I'd go several times in the summer. I didn't get home very early; there were many stops on the way. The last one was at Perkins Mills. Of course the drinking didn't bother me I was only a kid then. I used to stay up at the cottage with my older brother and a shanty cook. Dad and Mother only came up weekends, so they didn't know what lime it was when I got in with Bouchers, but it was a late night for me. I had great fun though. It was different in those days, you know. They used to have a canteen a little hotdog stand on the beach at the end of the lake and as kids we went down there every night until three or four in the morning. I never saw liquor. I really didn't. We'd have a soft drink. Now, today, kids don't know how to entertain themselves. We'd have a hotdog and build a campfire and sing songs. Frank Boucher, Sr., lived right across the road and he'd come over, and he had a fellow from New York that stayed there a lot with him and they'd play guitar for us. They'd bring a drink, but I never saw the kids, and I'm talking kids of seventeen or eighteen or nineteen, with a drink. George Boucher used to tell the story of Alex Connell borrowing Frank Ahearn's good 'coon coat, a beautiful thing. Connell took it down to the tailor's and had it altered to fit him. Ahearn was a big guy and when he tried to put this beautiful 'coon coat on again well, you can imagine! George was coaching hockey in St. Louis one time and a fellow wired the toilet seat and one of the big guys came out and sat on it from out of the shower and it gives him a jolt and jee! It nearly kills him! Old Frank used to talk about Ching Johnston. Two minutes to go before the game he would say to Les Patrick, "You're not going to play me," and he would drink everyone's beer, and go back to the dressing room just before the game and he'd take all their false teeth and he'd put them in different glasses one over here and one over there and switch them all around. Of course, in those days they'd had so many teeth knocked out, they had no protection, that they were all probably wearing false teeth. And there would be pandemonium before the game as they tried to find their own false teeth! Another time they were |

|

|

Born in Ottawa, 1901, Frank Boucher

(left) was a member of another hockey-playing family

George with Ottawa, Gilly and Bob with Canadiens, Frank with Vancouver

and New York Rangers, He won the Lady Byng Trophy so many times he was

finally given permanent possession of it George Boucher (right) was a great halfback with the Ottawa Rough Riders before he joined the Ottawa Senators in 1915 to become an outstanding defenceman. His team won the Stanley Cup four times. He ended his playing career with the Montreal Maroons and Chicago Black Hawks but returned to Ottawa to coach the Senior Senators to an Allan Cup victory in 1948-49. |

|

catching a train at Chicago to get to New York that night right after the game, and he went in to the dressing room early and cut all their pants off at the knees. And they had to go like that! Dad always went to Ottawa for hockey games when The Senators were playing. He had six tickets right in front of the Governor-General's box, on the boards there. Bill Beveridge was goalie and there was Allen Shields, there was Ted Leach from Niagara Falls, there was Kiminsky, there was Shannon, and Bill Touhey with the comb. Oh cripes! He never came on the ice that he wasn't combing his hair! He'd have a little comb and he'd step on the ice and he'd be combing his hair. And the two Roaches were there when I used to go, Des and Earl Roache. Old Frank Boucher and the two Cooks were playing for The Rangers there, and then when the Quebec Senior League took over, I had seats there but I moved up one row behind the box because it was different pucks then. As long as the Senators were there, I used to go to every game. I never missed one. Frank and George and Billy Boucher, they were really a very sporting family. Then I think there was a brother Carl that Jived in Aylmer. One time Carl's wife sent him down to the corner store in Ottawa to get a loaf of bread and a pound of butter and he never came back. George was playing with The Rangers then in New York, and one day at practice he looked up and he saw Carl in the crowd. He was with Ringling Brothers! And George talked Carl into going home, and when he went home he arrived in with a loaf of bread and a pound of butter. He'd been gone nine years! Carl had run away with the circus. One time there was a guy going all around here saying he was Billy Boucher. I was just married and came in and he said, "I'm Billy Boucher." I said, "Oh, that's good." So he told me that he had come down to Buckingham and met a bunch of the guys in the Palace Hotel and had overspent and hadn't enough left to get him back to Ottawa. He said, "Could you lend me ten or twenty bucks?" I knew there had been a guy going all over the country, including Montreal, imitating Bill Boucher, and he was said to know more about the Bouchers than Bill did. "Oh," he said, "you're a friend of George's. You're always at this place at McGregor Lake." I said, "Well, I haven't got any money on me, but are you going to be around for a while?" He said, "Oh yes." So I said, "I've got to go to the bank after my dinner. If you want to wait until two or two-thirty and come back, I'll give it to you." I got on the phone and I phoned Bill Boucher because I knew him. He coached the Aylmer Hockey Team when I was a manager of the Junior team here. And Bill said, "Can you keep him there?" I said, "Well, he's not supposed to come back till two-thirty." He said, "I'll be right down." So he brought that big policeman in Ottawa, a detective he's dead now Bill Hobb's sidekick. I said, "I watched where he went and he went into the Palace Hotel. I think he's till there." So they went up and they arrested him. Well, the Ottawa police couldn't arrest him because they didn't know him. But he passed bum cheques and he always imitated Bill Boucher and they put him in the jail here. Bill was boiling and he wanted to go in. "Let me go in there. Give me ten minutes with him and then you can have him." They nailed him. That's a long time ago.

J.D. Dunfield of Ottawa, in October 1992, Looked fondly back on the Ottawa Senators of the early 1930s:

I lived on the corner of Metcalfe and Waverly, which was about four short blocks from the old Auditorium. I believe the Old Ottawa Senators must have often played on Saturday nights because I was not allowed out on the weeknights while going to school. With my small weekly allowance and the profits from the sale of the Saturday Evening Post, I was able to purchase the 25 cent "rush-end" standing room tickets. If you arrived about an hour before a game you could usually find room to stand up against a steel hand-rail about half way up the end zone at the south end of the rink. This was the best position to secure the odd hockey puck that ricocheted up into the stands. Thank goodness the players did not use the"slap" shot in the 1930s as there was not any protective glass around the boards. Of course, the goalie did not wear any face mask and the forwards and defence might have had Eaton's catalogues under their stockings for shin pads. The care of the ice was labor intensive. After each period three men would come out with long-handled brooms which had faggots or twigs tied around the end of each pole, with a wide sweeping motion the three men would work their way from one end of the ice to the other end, after which the small ridges of snow would be pushed down to one end with handplows and shoveled into a trap-door behind the goal posts just off the ice surface. There were only six teams in the N.H.L. in those days and Ottawa was in the "Big League." At one time Montreal and New York City had two teams but it was generally a six-team league. Player trades were not common and you could remember the names of most of the players on each team. Ottawa was the cradle of hockey talent with the Finnigans, Kilreas, Cowley, Beveridge, Connell, etc., filling the rosters of many teams.

Budge Crawley, the great Canadian film-maker, once told me of an encounter with three Ottawa Senators off ice that forever changed his life:

I was just a little gaffer about ten when my father (he was chief accountant for lumber baron J.R. Booth) decided that my table manners had improved enough to allow him to take me out to dinner. At that time the Tea Gardens was the place to dine in Ottawa. |

|

During his 1927-28 year with the Ottawa Senators Alex Connell set a goaltending record, registering six consecutive shutouts. He was known as the "Ottawa Fireman," partly because he worked with the Ottawa Fire Department and partly because he "put out the fire of opposing marksmen." |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Hector "Hec" Kilrea starred for Tlie Senators in the late 1920s and early 1930s before joining teammates Frank Finnigan and Frank Clancy with The Leafs. He was said to be "a merry man to all the maidens dear. " |

||

|

I discovered that the pre-dinner rolls were unlimited and was well into my seventh or eighth when a big fight broke out on the balcony above between the Ottawa Senators {my father identified them: Frank Finnigan, Harold Starr, Harold Darragh) and the Chinese men who owned the restaurant. At first they used their fists. One of the Chinese men came right over the balcony and down on the tables below. Can you imagine that! Real cowboys and Indians! Then the Chinese men went into the kitchen and came out with their red-hot pokers. I don't remember much after that. I suspect that the restaurant diners cleared out and that my father led me away. But I know now that that was the beginning of my film career.

From as early as I can remember my mother was a loyal fan of I. Norman Smith, both as a writer and as a representative of a paper with integrity. She dipped out and kept many of his great Saturday "Window" editorial page pieces which appeared in The Journal. Although she never spoke it, she must have been pleased when the late Tom Lowery hired me on the at The Ottawa Journal as a general reporter. I, too, in my turn cut and clipped some of the best of I. Norman Smith and the other day, in the manner of those coincidences which are not really coincidences but which occur in so much of my life, while working on this hockey chapter I opened an old file and there fell out Smith's tribute for the passing of Tom Lowrey from the Ottawa scene, November 7, 1981. Smith's reminiscences moved me deeply and his closing paragraphs made me wish that I might have been party to, or even overheard, the great sports talk that went on in The Journal editorial offices in those days:

Early Sunday evenings after a big Ottawa sports event a wholly sober talkfest took place at the far end of the big newsroom. Grattan's (O'Leary) favorite perch was on the coil by the window; others nabbed chairs, sat on desks, or in a standing-room-only situation, held up a wall. According to the year there would be Tom (Lowrey), Baz O'Meara, Walter Gilhooly, Bill Westwick, Bryan White, Eddie McCabe; outsiders like Father Armstrong, [Mayor] Stan Lewis, Jim McCaffrey, and a Gorman. We told our wives we had to go down to check or write something, and sometimes we did. But really it was to get together in the hope we might once again listen to the sights and sounds of Dey's Arena and hear tales of King Clancy, Jack Dempsey, Frank Amyot, Eddie Gerard, the fabled Mike Mahoney and even of sports writers. But about that time the night staff claimed it needed the newsroom to get the morning paper out.

In the winter of 1988 it was far too late for me to gather together such famous hockey buffs or to try to recreate a milieu in which such rich sporting talk would be inspired. But I did manage to gather together some men from different walks of life, and different age groups with a wide knowledge of the sport: Roy MacGregor, sports writer and columnist for The Citizen: Bob Wake of Carleton University, a hockey buff for sixty years; and the two Finnigans Frank, "The Old Pro Alive," and his son Frank Jr. In this "hot-stove" conversation, they bring back to life the glory years of The Senators:

Frank Sr.: Eddie Shore quite a hockey player. Frank Jr.: He was big. He was good and he was tough and he was Mr. Hockey. He was very much like Bobby Orr. He could stick-handle, carry the puck same as a forward. Frank Sr.: All our defencemen in those days could carry the puck the same as a forward. When the puck went into our end the defence didn't wait for a forward to go back and pick up the puck. They rode out, they broke out themselves . .. Frank Jr.: Remember, you could pass as far as your own blue line. Now, the defencemen, they don't want them carrying the puck too far so it's a different game. No doubt Orr was as good as I've ever seen. But Shore was tough. Bobby Orr wasn't what you would call rugged Shore was MEAN. Frank Sr.: "Here comes Shore." My game plan was to check him down my wing the same as everybody else. But he'd probably come down the way Orr used to and score just the same as Orr would. But Shore was aggressive. Roy: Frank, if you had to check Eddie Shore and you grabbed a hold of him, how quick would they be to call a penalty? Frank Sr.: Well, not the way they call them today. They seemed to let a little more go in those days. There was more bodycheck-ing in those days. Today if they grab your stick, they get a penalty for it. In my day I might have grabbed the odd stick . .. Frank Jr.: That's where they brought in that rule: only two steps before charging ... Frank Sr.: Red Horner could cany the puck just as well as a forward and oh, a pretty big fellow . .. Bob: I saw him play a game against Canadiens in Montreal and Canadiens had fast-skating forwards. They were beautiful to watch. And every time they got down past the Toronto blue line, Red Horner would just wrap his arms around them and the referees let him get away with it. Frank Sr.: He got away with a lot knees and stuff, too, you know. Yes, he did. He was really one of those rough hockey players |

|

J.J.Jack Adams (left) was an

outstanding player before he became one of the N.H.L. 's innovative

executives. He was with Ottawa's Stanley Cup winners in 1926-27; then went

on to put Detroit Red Wings on the map, as coach, manager, developer of

the farm team, and Gordie Howe. Another Ottawa great, Clint "Benny" Benedict (right) spent seventeen years in the N.H.L. playing on four Stanley Cups, three with Ottawa and one with Montreal Maroons. Born in 1894 Benedict moved into senior ranks while only fifteen years old. He was the first goalie to try using a face mask. |

|

|

that's what stood out for him. It wasn't that he was as spectacular as Hap Day or King Clancy... Frank Jr.: But he kept them honest, Dad. That's what you got to have. If you let them run all over that rink, you are in trouble. Frank Sr.: The only way they will play honest is to let them make the rinks bigger another twenty feet wider, twenty feet longer. Frank Jr.: Oh, Dad, you're exaggerating! You couldn't make them that much bigger. It's true they are making hockey players bigger big as basketball players but still. . . Roy: But I want to know about not wearing helmets, not wearing masks. Frank Sr.: They should have in my day. I protected myself. I skated pretty low and they hooked, you know, up that way, and got me. Frank Jr.: When I was playing, some fellas were wearing helmets, in the '50s. |

|

One of the N.H.L. 's colorful tough

guys, Sprague Cleghorn (left) had a truly chequered career, playing

alongside Cyclone Taylor with the Renfrew Millionaires and with Ottawa's

Stanley Cup greats in 1920. When he joined The Canadiens in 1922 he took

on a vendetta against Ottawa. Many brawls resulted. Frank Finnigan's admiration for his opponent Aurel Joliat (right) knew no bounds and grew with time. The "Mighty Atom" or "Little Giant" was born in Ottawa but played for the Canadiens on a line with Howie Morenz and Bill Boucher. He played on three Stanley Cup teams and was on one first and three second All-Star teams. |

|

|

Frank Sr.: I remember back in the Senior City League days there were fellas that played for the Hull Volants and the Hull Canadiens they wore helmets, not all, but some. Roy: Charlie Burns that played for Detroit, he had a steel plate in his head, and he always wore a helmet. And then there was a goaltender in your day, Frank, Clint Benedict. Frank Sr.: He got an awful hit one of the Canadians a puck. Roy: Interesting. You're saying they should be made to wear masks. But I can't help thinking that in your day, when you had a guy in a corner and you had a real good chance to nail him, something would go up in your mind and you'd say, "I can't really hit his head, or his face." Would you think that? Frank Sr.: You'd think that. Yes. I never thought of swinging a stick. In those days, very few did. Roy: Sprague Cleghorn didn't bother him to swing a stick. Hooley did. Playoffs against Boston. Frank Jr.: What happened when Hooley Smith was suspended that time? He was suspended for ten games. Quite a blow. Ten games out of a thirty-five-game season. Now they'd get ten years. Must have been a pretty vicious blow. Bob: Frank, could you skate faster than Hec Kilrea? Frank Sr.: No. Well, maybe if I got under way, faster. On the Ottawa River, for instance. I could skate with any of them. But Hec broke fairly fast and he was a terrible skater. Bob: In Montreal, between the periods, they used to have these races. Remember? And Hec Kilrea won that. Roy: What would other players have said about you? What would they have said Frank was so good at? Frank Sr.: Well, I was known as Fearless Frankie . . . Selke said I was the "Coaches Dream." Roy: Where does the "Fearless Frankie" come from? Frank Sr.: I was, well, I guess I played pretty aggressively .. . Frank Jr.: I always heard that Dad was always very hard to knock off his feet. Dad always used to say, "I skated low with my feet wide." Bob: How did you get the name "Shawville Express." Frank Sr.: Well. I used to play for Montagnards and for Ottawa University and I used to come down on the PPJ (Push, Pull, and Jerk) to the games. When I played for Ottawa University I was in the Commerce course they signed me on there it was all Irish then. The French were only starting to come in and they were battling . . . and I took courses there. I'd touch the typewriter keys a few times and open the odd book because we had to do that in order to or they would have called us "tourists." And we couldn't play for Ottawa University unless we were "going to school." Lionel Chevrier was my center ice player for Ottawa U at that time, and Ladoucoeur from Hull was my left-winger. Roy: For the University of Ottawa. You got a degree then? You had to learn typing. Did you learn to type? Frank Sr.: They'd just give us a piece of paper the day we came down and we'd copy that. We got sixty dollars a game for that. . . Arnprior wanted me to go over to play for them. They were going to force me on territorial grounds. But Dave Gill was then the head of the Senior League Ottawa and District, and Gill was manager of New Edinboroughs. So Dave said, "No, he'll play in Ottawa. That's the closest Senior League. Arnprior is only Inter- |

|

Ottawa University team in Ottawa City Hockey League, 1922-23. Top Row, LEFT TO RIGHT J.P. Coulson, Rev. A. Garry, J.Reynolds. Second row G. Bolam, A. Lajeunesse, G. G. Lafrance. Third row - A. Ladoucoeur, L. Chevrier, F. Fittntgan. Fourth row W. Desu, G. Soubliere, H. Findlay. |

|

|

|

mediate and he's beyond that. A step back." So he protected me. Then I went to Montagnards and that was the year The Auditorium was built, 1923. They gave me a thousand dollars and then they paid my up and down expenses on the train and my expenses for a room we stayed at the old Russell at that time. So then when I went with Montagnards the next year I was two years with Ottawa University Dave Gill, head of Senior Amateur Hockey, said to me, "I'd like you play for New Edinboroughs but I know you've been getting so much from Montagnards. But we can't match that, so you go ahead and play for Montagnards." The butchers on the By Ward Market were putting up the money for Montagnards. |

|

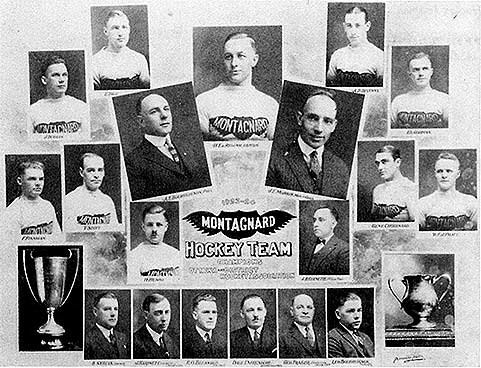

Montagnards, Champions of the Ottawa

and District Hockey Association, 1923-23. Bottom row, LEFT TO RIGHT S.

Seguin, Trainer; J. Harnett, Chairman, Sports Committee; E.P. Belanger,

Sec. Trea.; Dave Lqfreniers, Second Vice-pres.; George Fraser, Chairman

House Committee; Leo Bourguignon, Trainer. Second row R. Huard; J.B Cuenette; First Vice-Pres. Third row Frank Finnigan; V. Scott; A.E. G Bourguignon, Pres., J.E. Morris, Manoger, and Coach; Gene Chouinard, W.F.J. Pratt. Back row J. Brennan; E. True; H.E. Reaume, Captain; A.D. Devenny, Ed. Gorman. |

|

Frank Jr.: The old Montagnards Club was on the corner of Cambridge and Somerset, a sporting club with a license. You bought a membership, two dollars, and you went there, and had a beer and shot the breeze. When I played Junior for Montagnards, we were not allowed to go there but the Seniors were. Mr. Rip Riopelle was the manager of the club then, Rip Riopelle, personnel manager of Air Canada now. He was quite a hockey player Senior here and he had a cousin, Howard Riopelle played for Montreal. Frank Sr.: Old Tom Murray of Barry's Bay was a good friend of mine. His whole ambition was to play baseball, turn pro. Catcher. He was a good catcher but, well, baseball wasn't a Canadian game. At the time he had Bill Skuce pitching for him, in the Ottawa City League, but he also used to go up and pitch at Barry's Bay for Tom. Roy: He must have been an amazing physical specimen, Tom Murray. He was one hundred and still going . . . Nelson Skuce over at The Citizen also is a great pitcher. Bob: Any of you guys ever get chased out of town after a ball-game? Roy: Oh, I've had police escort to the cars. Bob: In Chicoutimi they used to put us on a high-bodied truck. You know, during the game a little excitement, a little ugliness .. . Roy: It happened in the Arena. It wouldn't happen where Frank played on such high levels as he says, "I played with the best" but where it's not good hockey, there would be terrible fights and the police would come. Frank Sr.: We never had any fights. We used to have referees come up from Ottawa, but then our league bust up during the First World War. I was only fourteen when I was first playing in the league with guys who were sixteen, seventeen, eighteen. Shawville, Quyon, Campbell's Bay, Fort Coulonge, Portage-du-Fort. Shawville was the only place on the line that had a covered rink, do ya see? |

|

One of the many hockey players who came

out of Ottawa to star in the N.H.L., Εbεοεγεr "Εbbiε" Coodfelloow(Iefl)

was born there in 1907 but only played amateur with Montagnards before

going on to his long successful career with Detroit Falcons and Red Wings.

He was on All-Star teams, won the Hart Trophy, captained the Red Wings for

five years, and was on three Stanley Cup teams. Ralph "Cooney" Weilands' (right) hockey career took him from Seaforth, Ontario, where he was born, to the Ottawa Senators, 1932-33, to Boston for the Stanley Cup Championships of 1928-29 and 1938-39, to Detroit for a year, and finally to Harvard University as coach. |

|

|

The first money I ever earned was when I was thirteen and Quyon paid me to play against Fitzroy Harbour for money under somebody else's name. I was under age, only about a hundred and thirty pounds, so I had to take somebody else's name for Quyon. Ten dollars. And Quyon lost. We were playing against men. They came across on the ice to us. There was no power plants in those days, so it was safe crossing in a car. The ice isn't sitting on top of the water, so it cracks and goes down if you try to cross with a car or a team of horses. It was easy to maintain a nice road in those days, BOB: There couldn't have been as many fellows as good as you playing at thirteen. I'm curious how you got so good. There were no teachers, no coaches ., . FRANK Sr.: Well, I played all the time on ponds and on the streets. No coaches. I guess I got better and better all the time. And we used to play on small rinks and you had to be a good stick-handler to get around no room, no ice surface .. . And I was playing with fellas a lot older than myself. You learn from them. You improve. I was playing with fellas ten years older than myself. Even on the ball team, I was playing with guys ten years older than I was. Dougal McCredie was ten years older than I was, Clarence Caldwell was ten years older than I was . Bill Cowan, Larry Hynes, Hilton Findlay, Clifton Woodley, Charlie Bowan, they went to play with Ottawa University too. But at that time you had a pretty fair Intermediate league; Pembroke, Arnprior, Carleton Place, Perth, Smiths Falls they all had pretty fair hockey clubs in those days, and all Senior clubs were in Ottawa, a league at Minto Rink and then at Dey's Arena another league, and then they played off... All we did was play hockey in the winter. BOB: But there was no talk about how the game should be played. You just went out and did it. Frank Sr.: That's right. You had a coach or a manager, you know. But what did he know? Frank Jr.: He changed the lines. Frank Sr.: And in those days he didn't change too many lines! Frank Jr.: And opened the doors ... FRANK Sr.: That was just before the seven-man hockey went out. Around 1912 I guess the Silver Sevens were playing seven-man hockey. I never did. Johnny Quilty's dad played seven-man hockey Bobby Quilty a Silver Seven. By the time I started to play for Ottawa the manager and the coach were in place. Managers didn't have to be a star to be a coach. The same in baseball if you understand the rules and know the game, some fellas become a coach. In my day P.D. Green was coach when I first turned pro, then Alec Curry, then Newsy Lalonde, then Dave Gill. He was both manager and coach. The thing with a coach is he can't tell you what to do. He can change the lines but if you're on ice playing your line he can't tell you "pass that puck." You know it before you get there. You know what |

|

All Star "Stars" in the Ace Bailey Benefit Game, 1934 at Maple Leaf Gardens. Back row Chuck Gardiner, Red Dutton, Eddie Short, Alien Shields, Βill Brian, Lionel Conacher, Ching Johnson, Nels Stewart, Frankie Ftinnigan. Second row Larry Aurie, Hooley Smith, Jimmie Ward, Lester Patrick, Leo Dandurand, Bill Cook, Howie Morenz, Aurel Joliat, Herb Lewis, Howie Morenz Jr.

|

|

|

|

you're going to do. You've got your mind on it. The coach can tell you this and that, but you don't hear when you're on ice. We had practices, but again the coach didn't do a hell of a lot. He would get you to go up and down the ice, and maybe take a man off so you could play short-handed. Keeping in shape in those days was up to yourself. There was always somebody coming up who could take your place, so you kept yourself in shape. If you hit the dope or the liquor on the day before a game, you were only hurting yourself. Lots of fellows in the older days, before my time, some of them hit the bottle pretty hard before a game, and of course they didn't last so long. The odd fellow would smoke but not to excess. It kills your wind. And you know that. You were your own judge of when you were in shape. If you couldn't do that, you wouldn't make the team. That's why we all played baseball and tennis and hardball, even golf, in the summer to keep in shape. Bob: I'm curious about the fact that what you're saying is that all this was done on some kind of basic innate talent you must have inherited. You weren't taught. I wanted of ask you whether when you were playing hockey or even practicing, or even before the age of thirteen this may sound foolish but did you think about what you were doing? Frank Sr.: Yes. I always wanted to make pro. When I would get the paper and see the Smith Brothers and Bruce Stewart and his brother and Punch Broadbent and Cy Denneny, and Frank Nighbor and Eddie Gerard and Buck Boucher and Jack Darragh ... Bob: There was none of this stuff of the older player taking the |

|

The Senators of the early 1930s were fondly portrayed in a series of cartoons in the Ottawa newpapers. | |

|

younger player aside and giving him advice. I'll give you an example. Remember Billy Dineen he's a coach now and his brothers are playing in the N.H.L. now? And the story I got, rightly or wrongly, was that one of the things they couldn't break Bill Dineen of doing was that when he came down to the defence, he always cut outside. He never cut inside and this meant that he got shoved to the corner by the defenceman. Now, the guy who was telling me this story told me that Bill Dineen was told many times not to do this, but he could never break the habit. Frank Sr.: Your coach could tell you things, but if you didn't have the ability to learn from that well if you didn't learn how to go in on this side and this side and mix it all up and cut in different sides different times, then you fox him, and then he knows you aren't always going to do the same thing . .. FRANK Jr.: Bill Dineen from Ottawa went down to play with St. Mike's after he finished with St. Pat's, and when he was finished playing with St. Mike's he played with Gordie Howe, so he had a pretty good teacher. If he could learn anything, he could certainly BOB: How old were you when you began to learn all these things you're telling us now? Frank Sr.: It would be a couple of years after I turned pro. You get a little smarter. But if you haven't the ability to improve yourself, you just don't make it. Frank Jr.: You didn't have the time either, Dad. You were only playing thirty-five games a year then, so you had to learn fast. |

|

|

|

Now they play eighty, and the practice sessions that you'd have then compared to now you learn a lot from watching other people, too, you know. You watch somebody's technique and then you try to copy it, see if it works for you . .. Bob: Did you have specific game plans in your head? Did you say, "Here comes Morenz and with him I have to do this and that?" Frank Sr.: Sure, with Morenz I always had to be a couple of strides ahead of him, and I'd go up, and I'd try to run with him, because if I started with him, then I was soon thirty feet behind! And he always came down my wing the left-hand side and he played center ice and he'd go back and he'd come down at a terrific pace. He was an awesome skater, he'd go so fast. So, anyway, he'd go back after making that rush if Toronto had Morenz today he'd get them out of their own end anyway, he'd go back and say "Give me that puck!" And he'd come down again, and gain maybe the third time. He was terrific. But I always put him into center and Nighbor had this poke-check they haven't got anyone in the league today who can check like that but, anyway, I'd shove Morenz over to Nighbor, and if I didn't pick him up, Nighbor would with his poke-check, so he would have to go through the defence then .. . Bob: How did you get from Montagnards to playing pro hockey? Frank Sr.: Well, of course, they were always looking me over and then I was playing in The Auditorium where the Ottawa Senators |

|

|

|

were playing, and I looked pretty good I was twenty-one so, anyway, they called me in Shawville. BOB: Well, so far we've gotten out of you what it is that you were noted for. So let's try statistics. Frank Sr.: My best year would be around twenty-one goals. I was up in the first ten for three or four years. Morenz, Joliat, they were ahead of me, of course, I was an average scorer no, maybe a little better than that. I might have been called a really good defensive player .. . Frank Jr.: When Dad went to Toronto he was brought there more for defence they had a big line "Kid Line" in Conacher- Jackson and Primeau. Dad was taken there to bolster a defensive checking line. Frank Sr.: We had Bailey who got hurt: Shore took the feet from under him. We had Harold Cotton and Harold Darragh on one line and for penalty killing we had Andy Blair, Bob Grade, and myself. The Thoms-Boll-Finnigan Line came later. The Kid Line was such a scoring line they were dynamite. Roy: Would you be there the night Ace Bailey was hurt? Frank Sr.: No, I wasn't. But I was there the year before, on loan. Ottawa Senators disbanded for a year and I went to Toronto, then back to Senators. They got money to go again, and then they folded and I went to Toronto. Bob: I was a kid up North in Chicoutimi when Ace Bailey got hurt and I've seen this argued by sports writers Toronto's Andy Little and he said he really didn't know what happened. I wonder if you have any impressions because this was a horrendous event. Frank Sr.: There was a little melee, shoving and pushing in the center of the ice. I wasn't there, but they have told it to me often, and I've had people try it on me to show me how it happened. Anyway, Bailey was standing there, and a few others in the center of the ice, and Shore came up and just took the feet from under Bailey, and he went up in the air and down and hit the ice and fractured his skull. Shore didn't intend it but that's what he did. He intended to give him a flip. Bailey never got over it. He was time-keeper at Toronto for years, and he coached. He just couldn't play hockey again because he has a plate in his head. He was lucky there were great brain surgeons in Boston at the time. Frank Jr.: Tim Daly, the old Maple Leaf trainer at Maple Leaf Gardens, he said that you"only used one stick a year." And he said, Finnigan would come in and unwind all the tape on his stick and he would sit down this was a pre-game ritual and he would sharpen his stick! Now why did you do that? Frank Sr.: Well maybe I wanted to take a little piece off the toe of the stick because sometimes I wanted to pull the stick up fast in a game and, if that little tip wasn't taken off, the puck would go under it. So when you went to take a pass in close to your feet, if that little toe wasn't the right shape, the puck would go under and you'd lose it. I used a jackknife and then wound the tape all around again. Maybe Γ used one stick a year, but they lasted a lot longer then. They were good sticks. They were good sticks. They were all one piece but sometimes you'd get them that they weren't balanced, so I did a little carpentry on them my father was a master carpenter, you know. I think they were made of ash. And Alex Connell, he was a pretty good RC, and we used to generally eat together at the Waldorf Astoria, that was the old Waldorf, not the new one and we'd have filet mignon, stuffed oysters, and strawberry shortcake in training before the game, you know and we'd have a stay-over in New York because we would be maybe going to Boston two nights hence. And it would often be Friday and after we'd eaten the steak I'd say to Connell, "Jesus! Alex, this is Friday! You shouldn't have eaten any of that." And he'd say, "You son of a bitch, you should never have mentioned it!" A great goalie. Hainsworth and Ted Benedict too. When they were making up the new Montreal Maroons, Punch Broadbent went down there and Ted Benedict, too, and he got hit very hard down there. That's when he started wearing the mask. Eddie Gerard went down and he was coaching them; Sprague Cleghorn hit Eddie Gerard across the throat there with his stick and Gerard lost his voice forever. Gerard was quite a defenceman for Ottawa. Bob: I was in Montreal when Howie Morenz ran into the boards at the back of the rink, broke his leg, went in to the hospital, and died. And there were two stories that I heard. One was that he died because of the effects of the broken leg, which sounds odd, and the other one was that his friends brought so much alcohol into the room to him that he died of that. Frank Sr.: I think that is right. I can't be sure. I was at the funeral in Montreal Forum that is where he was waken center ice thirty thousand people filed past, and from what I can understand, maybe he had a few drinks and had a blood clot. Roy: What was it like to be famous in those days? Frank Sr.: People always used to like to say they knew me. But they didn't know me at all. ROY: But they wouldn't write yon up the same way like "Frank Finnigan has a drinking problem." As a journalist in those days they wouldn't write that kind of stuff, the way they would today. FRANK Jr.: No, because Frank Finnigan would probably be down to the paper the next day and shove the paper down their throat. ROY: It was so different then. The press wasn't so close, and they wrote you up as a hero. And the young kids in the rinks, they'd know who you were from your face. Frank Sr.: And they had the gum cards and the cigarette cards. Roy: There was a conspiracy of silence, of respect. But not today oh, I used to cover sports ... I was at a game when Phil Esposito came running after Earl McCrae. Earl had said before, "Roy, don't go near Esposito. He's mad at sports reporters." And I was going to the restroom and Earl was right behind me and Esposito saw him and came charging up with his stick and Earl ran out of Maple Leaf Gardens as fast as he could go and I never saw him again . . . What do you feel when you watch a game now? Frank Sr.: I like it now but I think it was better in my day. Today it's a business. But I think there were better hockey players on the teams in my day they could take a pass, give a pass, play anything there are so many teams today that hockey's watered down the size of the roster for each team, twenty-five players, four lines, six or seven defencemen, changing the lines all the time. You had three lines in my day, four defencemen, a couple of utility players. Frank Jr.: In your day seventy-five per cent of them were excellent hockey players. Now you're getting fifty per cent maybe good players, and the rest are "grinders." Ten on each team are first rate; the rest are grinders. Roy: We've gone from sixty-minute men to guys who are only on for three minutes. How much would you play? Frank Sr.: If your line started, you'd play around twenty-six minutes. Roy: There's only a couple of men in the N.H.L. who would have that amount of ice time. Frank Sr.: That's if your lines started. A fellow has to be on at least three or four minutes to even find himself in the game. Roy: There's another point. What value is a twenty-four-second shift? You have to be on for a longer time to be of any use. Frank Sr.: You can't be on for two minutes and never get a chance to touch the puck . . . Aurel Joliat played for Montreal Canadiens all his life. Morenz at center and Joliat on left wing. Joliat was getting a little bald and he wore a black cap; I used to, just for fun, hit him and knock his cap off. He didn't like it. but you had to slow him down a little, and that was the only way to do it. He could turn on a dime and he'd come back at you he wasn't a bit afraid guts, I call it. No, you could hit him pretty hard and he wouldn't quit. No, he'd come back. Bob: When I came up here in 1925 from the Saguenay Valley you were playing then, Frank, and I remember you. Being eleven years old then, I was memorizing the names of all the N.H.L. hockey players. Well, Chicoutimi is an isolated area and Shawvilk-is an isolated area, but out of my country that is the Lake St. Jean district there has been George Vezina, Johnny Gagnon, and one of the Lamarands. Now we could skate from October to March, so how come only four players from Lake St. Jean? And the Ottawa Valley has produced so many hockey players you can't count them. And incidentally you don't get them any more. Frank Jr.: The towns were closer together and they went on the train, and lots of times there were men ready with horses and sleighs to put some young lads on with some hay, and get them to games hockey-nut men. Campbell's Bay and Coulonge and Shawville fought for years, and Quyon .. . Roy: That's the key right there. The towns have to hate each other. Bob: I know I'm the only one from the Saguenay Valley but we had all that too. When the Chicoutimi team went down to play Jonquier, they had to get the police every time, to get the guys to the train to go back to Chicoutimi. Frank Sr.: Here in the Ottawa Valley you have so many towns together able to reach each other, all within a hundred miles of each other, or less. And all kinds of train connections. From Chicoutimi you could only get to Quebec City and Montreal. Before I started playing for Ottawa University they came up to Shawville. They had heard about me "pretty fair player" |

|

The late Mrs. Ira Merrifield with a cherished sculpture of her late brother, Hib Myths of the Old Ottawa Senators. Tlie Merrifields were the first settlers at Beeechtrrove, Quebec, up the Pontiac. |

|